Calcutta and Bengal

“The cities are well lit, Dazzling is their garland of light, But darkness pervades the country, Darkness is our day and night.”

—GOBINDADAS

By the simple method of counting heads, Calcutta is the second city of the Empire. Whether it is also the unhappiest would be more difficult to prove, but it could certainly lay a strong claim for that distinction.

Amongst its four million people one does not come across those who love their city, and have pride in it. Many of its people are not even Bengalees. The workers and coolies in the docks and mills, for, instance, in very many cases, are “up country” peasants from other Provinces, who have been driven by impoverishment and hunger to find work in the city and whose first thought is to leave and to return to their families in the villages. The conditions of the working people in Calcutta and the “bustees” they live in, are such as England has never experienced since the blackest days of the industrial Revolution while the less fortunate ones—and there are masses of them—live at little above starvation level and find their homes in tin shacks or on the pavements.

The clerks and middle classes mostly are Bengalees, more often than not Hindus, but even they have their ancestral homes somewhere in the country and are in Calcutta to supplement the meagre income of their family from some interest it has in land. Like the workers of Calcutta, they have the spectre of unemployment hanging over them now that the wartime boom is passed, and are fearful of losing their jobs and not being able to find another. Only the prosperous merchants and business men are really at home in Calcutta.

Although it is the Provincial capital, Calcutta does not belong to Bengal. It is a new, a largely artificial city. Two hundred years ago it only existed as a trading station on the banks of the muddy Hoooghly River and the East India Company was busy fortifying it for their coming struggle with the French. In 1756, Calcutta passed for the last time into Indian (though pro-French) hands when the newly constructed Fort William was captured by the forces of the Nawab of Bengal, but a year later, at Plassey, the Company was revenged and the British became supreme in Bengal. Robert Clive, who had gone to India as a clerk of the Company, returned to England “the wealthiest of His Majesty’s subjects” and began the era of the wholesale export of Bengal’s revenue and looted wealth to a foreign land.

Since then Calcutta has remained the greatest centre of British interests in India—until 1912 when Delhi took its place, it was also the capital of India. Army officers were the architects of its public buildings, even of St. Paul’s Cathedral which stands in its central park. The old walled and moated barracks of Fort William still function and, across the park and near the racecourse, is a tremendous domed edifice to Queen Victoria, its white marble gleaming again in the sun after the removal of its wartime camouflage. Overlooking the park are the clubs, stores and hotels for the “burra sahibs” and beyond and “out of bounds”, the filthy streets and tenements of Calcutta’s citizens and the docks, engineering works and mills where British capital still predominates. To anyone who has been in Calcutta since the war, there can be little doubt of the feelings of the Indian people of today towards this British domination. “Quit India”, the cry of Congress, has resounded during all the processions, strikes and demonstrations that have gripped the city. Many of these were called in protest against the court martial of men of the Indian National Army, the army formed on the Japanese side from prisoners of war to fight the British and whose members have become national heroes and whose leader, Subhas Bose, the all but successful liberator of India. Sometimes the city has been paralysed for days on end—particularly following those occasions when the police fired on and killed students demonstrating against the sentences on the I.N.A. men. Then, military lorries have been attacked and burnt and trains have been stopped, and there has been more firing and more deaths. During all this time the campaigns for the Provincial elections were on, with bitter antagonism between Congress and the Muslim League—although on the streets the flags of Congress, the League and the Communists had been seen, side by side, in common protest.

At the same time the working people, faced with the prospect of unemployment or slashes in their wages, have developed their Trade Unions which they have built up over the last twenty years and these Unions have become experienced and disciplined—an important portent for the future. The strike of the tramwaymen was an early one and a test case as it were, the most highly organised workers in the city against an important British company and the workers won. Since then there have been more bitter struggles in Indian owned concerns as well, and the municipal employees have also been involved. Particularly significant was the time when Calcutta was without its rickshaws for two full weeks. These rickshaw pullers are backward and illiterate village men who are in Calcutta doing an inhuman job as beasts of burden—when such men have organised and act so solidly together, then indeed the Trade Union movement has become a profound force amongst the Indian working people today.

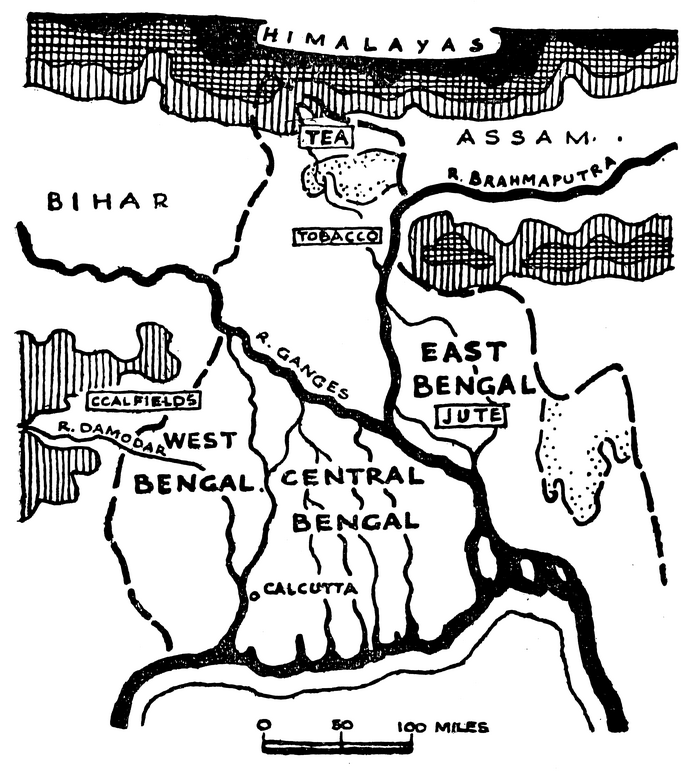

Virtually the whole of the industry of Bengal is concentrated in Calcutta—except for some coalfields in the Western corner of the Province—and Bengal is a great deal bigger than England and has some 60 million people. So seething Calcutta cannot give a picture of Bengal today. What goes on in Calcutta is far removed from the masses of Bengalees in the villages and rural towns. At the same time its existence largely depends on the villages—the jute mills, its greatest industry as well as the stronghold of British capital, draw their raw materials from the peasants’ fields. Jute is the second greatest crop, after rice—most of it from the flooded fields of East Bengal. But what does Calcutta know of these peasants and how it is produced? The city has a huge trade with the villages in rice and food, but in Calcutta are only the stores of the dealers and merchants—a whole series of middlemen exists between Calcutta and the villages. It is also a great port handling many of the peasants’ products—even from far beyond Bengal, for it is the outlet for the produce of the whole of the Ganges valley of Northern India. The railways, spreading throughout the Districts of the Province to bring the produce from the rural areas, are the only modern industrial penetration of vast areas of the peasant countryside.

Calcutta is the administrative centre for the people in the 86,000 villages of Bengal. It is the seat of the elected Provincial Assembly and of the appointed Governor, and, under Section 93, Mr. Casey ruled for most of his last year as Governor, without a Ministry. It is this administration that issued so many announcements that “Bengal has turned the corner”, that steps had been taken to ensure that the tragedy of the famine of 1943 could never be repeated. But do the peasants agree? Indeed what does famine mean to a peasant, what are the causes of his poverty and starvation, are these in fact being removed? The administration is full of schemes and plans for the improvement of Bengal while year after year areas of the Province are devastated by flood or drought. What is actually being done to improve the lot of the peasant? These questions of the administration are very important now that it is said that the British are ready to hand over India to the Indians. One can only understand what is involved in the demands to grant freedom to India, in the light of the way British administration functions now and the present realities of British rule.

Bengal is a land of mighty rivers, and of rich plainlands built up over the ages by these rivers bringing down silt from great mountain ranges. The Bengalee people of these deltaic regions are a single people in the sense that they have a language of their own—indeed they are as sharply demarcated as any of the many nationalities who inhabit India. One of their greatest struggles while under British rule was that against Partition in the years following 1905, when Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India, tried unsuccessfully to divide their land into two. However they are divided, almost equally, into two great religions, Hindu and Mahomedan—and in India religion and politics are to a great degree intermingled. There is a rather greater proportion of Muslims and the adherents of the two religions are not evenly spread over the Province. People in the towns and the middle classes generally are Hindus, whilst a very great proportion of the Muslims are peasants. However, in West Bengal Hindus form the majority of the peasantry, and everywhere they are present in considerable numbers in the villages. Amongst these common people in the villages, what basis is there for Hindu-Muslim differences, if indeed real differences exist at all? What support do the peasants give to the claims of Congress that it represents all sections of the people, irrespective of status or religion? What of the Muslim League which is demanding Bengal as part of Pakistan, a Muslim homeland to be divided from Hindu India? As well the peasants now have their own organisation—the Kisan Sabha. It is stronger in Bengal than in any other Province in India and had held its all-India Conference in 1945 in one of the Bengal Districts. How far is it a real force in the villages, and what is its policy?

It was with such questions that I left Calcutta for the villages and country towns. The election campaigns were to be in progress, and this promised to afford the instructive and interesting experience of observing Indian democracy, such as it is at present, at work, and of seeing the reactions of the people to the policies of the different parties.