Public servants or public masters

“Mother, my voice is choked with authority,

So I cannot sing my song.”—Written about 1906 for the Swadeshi Movement in Bengal.

In the cool fresh air of the evening it is pleasant to wander round the streets. After the stench and bustle that is Calcutta, the town is slow and sleepy. There is no traffic on the dusty roads, only the rickshaws making their way through the little groups of sauntering people.

It is Jessore, the heart of the once rich delta of the Ganges, and the chief town of the District of the same name (a District in India being considerably larger than an English County). All around are signs of a more prosperous past. Many of the old brick and stuccoed houses are dilapidated now—all in their time were the proud homes of landlords and of merchants.

A little triangular green where the Muslims pray lies in the centre of the town and right opposite is the most prominent building, the Police Station—or rather, the Police barracks. It is extensive, and seems secluded, even dignified, built in the pleasant, simple style of England of pre-Victorian times. Like the Courts elsewhere, the building has not long been redecorated, its walls a fresh yellow, the columns picked out in white. More sombre, but larger still, is the “Collectorate”, the sprawling offices of the District Magistrate and Collector.

Law, Order and Revenue—these seem to be the public buildings in one’s first glimpse of an Indian town.

We wander on, passing a small procession in the streets, the young men in white Gandhi caps shouting in unison, “Quit India”, “Jai Hind”. It is bright moonlight now and we go to see the river—the “Bhairab”, the “fiercely flowing river”—on which trade has flowed for centuries bringing wealth and produce from the villages. On the other bank the jail can just be seen and, quite recent additions, the Famine Relief Hospital adjoining the famine destitutes’ camp.

We cross by the bridge and see the broad sweep of the river. But beneath us is no water—from bank to bank is a mass of hyacinth! The river has died! Crumbling brick steps leading down to the edge of the water that once flowed bear silent testimony to the life the river used to have. Now, that lovely flower, the curse of the waterways of Bengal, has overgrown it—the fiercely flowing river!

Death and destitutes! Law and order! Is that all the picture?

The morning breaks. In Bengal the winter nights are cold—people in the streets are shivering still and draw their thin shawls around their shoulders. The rickshaw pullers stand waiting in the morning sun, alert for fares. A military lorry hoots its way through the town. Barefoot people collect in a little queue to get water from a creaking pump and little children run around with almost nothing on. A late shopkeeper takes down his shutters and a sweeper, with but a rag around his middle, is clearing out the open drains which run along the street.

We see more of the town. The elected bodies of the people—the Municipality and the District Board—have offices in modest buildings, invisible previously in the dark. There is a Public Library built from the money of an Indian donor, nearby a primary school in a converted building. The college functions in an old mansion and two large tin sheds, its proper building still is requisitioned. There are numerous offices of officials, in old houses mostly, Civil Supplies Department, Agricultural Officer, Jute Controller, Weavers’ Co-operative Society. A small comb factory closed some time ago for lack of raw materials and there is no other in- dustry, only by the station is the railway yard and a power house supplying electricity to the town.

The headquarters of National Congress are in a large house with the tricolor flag of freedom hanging out of an upstairs window—inside they are still haggling with the Police over the return of furniture and documents taken away when Congress was banned. The green flag of the Muslim League, emblazoned with the crescent of Islam, is displayed on their less pretentious building. Opposite the Municipality building is the little office shared by the Kisan Sabha (the peasants’ organisation) and the Fisherman’s Association. Elsewhere is a room for the Student’s Federation and, in a single storey old house, the District office of the Communist Party, its red flag on a long slender bamboo pole flapping lazily in the clear morning air.

Authority And Democracy

In Jessore then, as in every other District town, there are two kinds of administration. One, the District Magistrate-cum-Collector, the other, the elected District Board and Municipality. We might call the first “Authority” and the second, “Democracy”. To what extent does each govern the people? And how do the British rule with so few Britishers? (For on more than one occasion I found myself in a District which had no British official of any sort.)

This dual system of administration applies from top to bottom throughout India (or rather throughout British India for the remaining two-fifths of the territory of the country are Princes’ states under autocratic rule.) The Viceroy at the top is, in effect, the Collector-in-Chief, for he and the Collector have similar powers, one over all India, the other over a District. Side by side with the Viceroy is the elected Central Assembly and in each of the Provinces, such as Bengal, the Governor functions beside the elected Provincial Assembly.

In a District, as we have seen, there is the Collector and the elected District Board. Below this again are Sub-Divisional Officers (S.D.Os.) and Subordinate Circle Officers side by side with Union Boards—these latter are the lowest elected bodies and cover, say, twenty villages.

How power is shared between these two systems was made very clear to me on the occasion of a long and revealing discussion I had on this subject with three Circle Officers.

The Collector and District Magistrate, as his name implies, both collects revenue and administers justice, they told me. More than that he controls the Police, and is legally responsible for all administration in his District—in addition to what he administers direct, his task is also to ensure that the elected bodies carry out their work in a ‘satisfactory’ manner and if they do not, he has legal power to supersede them. In the same way, the S.D.Os. and Circle Officers have powers over the Union Boards. In the Province also, the Governor can supersede the Provincial Assembly—as Mr. Casey did under the famous section 93 when he ruled direct for many months without a Ministry.

My Circle Officers were interested when I told them how fundamentally opposed this was to democracy in Britain. There the Civil Servant is given his powers through an elected Parliament which can always check his activities, and he administers very largely through elected bodies. Also a basic and jealously guarded principle is the separation of those who administer justice and those who have executive functions, and control of the Police is completely out of the hands of those who judge the accused.

“A civil servant sits in an office then, and is little more than a clerk” said one, and he did not seem to relish their position as compared with his own. During our talk it had become more and more apparent to me that in front of me, were three men who called themselves Civil Servants but who in reality were Civil Masters. Later on in the towns and villages of Bengal I was to see how great a control the District Magistrate, the S.D.Os. and the Circle Officers wielded over the lives of the people.

The elected bodies, the District and Union Boards and Municipalities, are limited in their powers to such things as looking after secondary roads, education and public health. The money they can spend on these things they collect themselves through cesses and rates. But they collect from an

impoverished countryside which has already contributed to the revenue of the collector—even then they have to help pay for the police! For instance, on one occasion a Union Board President showed me his books. The annual income from rates was Rs. 2,500 a year. Of this Rs. 1,900 was spent on wages, mainly on village chowkidars—sort of watchmen- cum-policemen who legally have to be provided in every village. This left Rs. 600 a year to be spent on roads, assistance to primary schools and such like in about 18 villages—or about 3 annas per inhabitant per annum! As an example of the relative importance of different services for the people, it is interesting to note that, for Bengal as a whole and taking a pre-war Budget as a sample, while 12 percent was spent on police, 5 12 percent was spent on health and only 2 percent on primary education!

Little wonder that in Jessore the Collectorate was 50 big and the offices of the elected bodies so small! Moreover, recently there has been a growing tendency for the bureaucracy to take more and more out of the hands of the local bodies, particularly since the Governor has ruled under Section 93.

From Mr. Casey downwards the officials justify their actions by pointing out that these bodies are inefficient and corrupt and that the only way to get things better is to put in capable civil servants to run affairs, to centralise control to a greater degree, to “provincialise” things. We shall see later the results of this policy, whether in fact things have become more efficient, or whether corruption and inefficiency have not become hidden and so cannot be exposed by the people.

An examination of the methods of election of the various bodies is very revealing. The higher the body, the more restricted the franchise. A Union Board at the bottom is elected by every villager or peasant who has a holding large enough

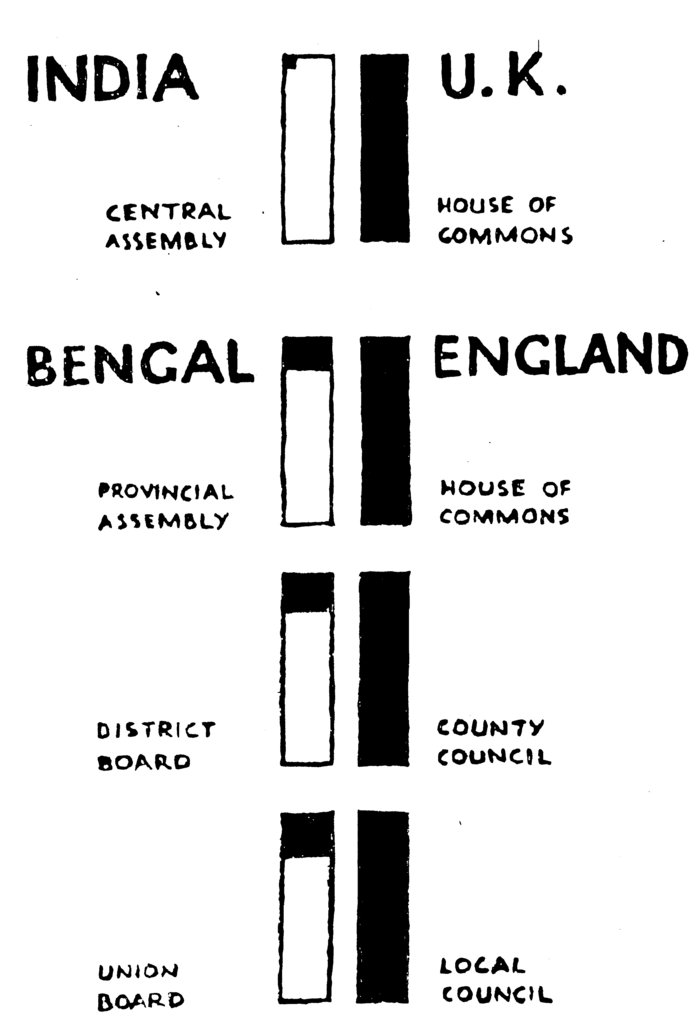

Figure 1: Democracy in Britain and India. The proportions of adult people eligible to vote for corresponding bodies in the two countries are shown in black.

to pay a rate, the “chowkidari rate”. But the Provincial Assembly is elected by under 15 percent of the people (with separate electorates for the different religious communities) while the Central Assembly for British India is voted in by less than 1 percent of the population! When these facts are coupled with the very limited powers of the bodies when they are elected, the picture of “safeguards against democracy” seems to be complete.

On more than one occasion when I was discussing the extension of the franchise with an official, he remarked, “you must give us time to prepare the election rolls”. This is fantastic when one knows a little of how they do the job at present. If left to themselves they would never prepare a roll for universal franchise in a hundred years. Many people eligible to vote are never put on the rolls at all. “Dead” names are written in and when rolls are being prepared, the public is hardly informed and individual protests get no results. For instance in one area I knew of a District town where there should have been about a hundred voters there were only six on the rolls! In a family I stayed with there should have been seven, but there were none.

I have no mind for law, but a talk I had with a pleader in a small town threw much light on the legal basis of British rule and of the powers of authority. He was an ardent nationalist and had worked in his young days in the Congress movement. We were in his house, which served also as his office, and beside him his one old clerk sat cross legged, writing out lengthy documents by hand. All around were ageing and weighty volumes of law, and, when he pointed it out, it was clear enough that the whole of this basic law is “British made”. He read some clauses in the Criminal Code so ably drafted by Macaulay. One says in effect, “if two or more persons carry out an illegal act, it can he treated as conspiracy”, that is, any type of crime can be judged as conspiracy against British rule. It is a punishable offence to inflame differences between classes, as of course a peasant does when he organises and protests against oppression by his landlord. Again to bring disaffection, hatred or contempt against Her Majesty means transportation for life. As “disaffection” is defined as “not affection” most of the Indian people could be transported and certainly the whole of the nationalist movement! Also in India, trial by jury is very exceptional and “special” tribunals can always be set up, as is done particularly of course for political cases. Such powers still remain and would seem to be enough for any ruler, yet, as he pointed out, new measures have been continually brought in, most of which give increased power to authority. During the War alone over 200 Ordinances have been promulgated and “rule by Ordinance” in different parts of India has been a very common feature for many years.

Does all this give that picture, so often painted by apologists for British rule, of an India advancing towards democracy, of Indians being given ever increasing powers to govern themselves? The reality is that administrators and civil servants, the police and dispensers of justice are given their powers, not by any democratic body of the Indian people, but by authority of the British, ultimately by the India Office and Parliament in London—and during and since the war they have even increased the scope of their activities. As for the elected bodies within India, they deal only with certain social measures for the people, but have not the means to provide them; they are elected only by the upper sections and they work within the framework of a law itself designed for the retention of the foreign ruler. It makes no difference that this rule of authority is carried out by Indians—in any case these are carefully selected for their integrity and are highly paid.

When the hidden but all powerful hold of British capital over India is also borne in mind, India can be seen for what it really is, the world’s greatest colony and subject nation.