Indians and the British

“Bengal is indebted to the enterprise and sound management of the jute mill industry for the fact of its being the wealthiest Province in India.”

—British businessmen in India.

(From the Annual Report of the Indian Jute

Mills Association, 1940).

The common man of Britain is a participant in the Indian scene no less than a Congressman or a Leaguer, an Indian peasant or a mill worker—for India is ruled in the name of the British people. Yet many times I found that never before had the people in the villages and towns been able to talk to a common Britisher—often I was the first they had ever seen. They were intensely interested to hear what the British people thought about India and how it was that they could allow it to continue in subjection for so long.

When a peasant had told me of the sufferings of his family and his village and then asked me about the people in Britain, I would have to put a complicated situation as simply and correctly as I was able. There are two sorts of British people, I would tell such a peasant, the common people, many of whom are workers in large factories, and the big men who own these factories and also have most of the money in the banks. So these men are very powerful and the common people who work for them struggle against them and have Trade Unions—in the same way that the Indian peasants have their Kisan Sabha. These same sort of big men get profit and wealth out of India also and exploit the common people there—so the peasants of India and the working men of Britain have the same oppressors and are comrades. They would ask whether the workers are poor, whether they starve and die. Yes, some are poor, I would tell them, and although they do not starve like the Indian people, often they can get no work and have a struggle to keep their family. Many do not get enough to eat and are cold in the winter, because they have not enough fuel.

How many British people would agree with what I told the peasants? They saw it clearly enough and were encouraged—they had never thought of a Britisher as other than a big official or a soldier. However, such a simple explanation would not satisfy an educated man, a local leader say, who closely followed British politics—for every question in Parliament about India or any resolution passed by an organisation in Britain is prominently displayed in the national press. Such a man might be acutely disappointed with the Labour Government. At first he had had such high hopes, but it had turned out to be as bad as any Tory government.

He might say it was even worse because it covered up what it was doing with so much talk and statements about its good intentions, whereas Amery did not even pretend to be anything else than an imperialist. Although the police had been firing in their usual way on demonstrations in different parts of India the Labour Secretary of State had refused to set up inquiries. Moreover under the Labour Government Indian troops had been used against the Indonesians (every Indian

I spoke to—whatever his views on other matters—saw the happenings in Indonesia as an attempt by the imperialists to retain their hold over a colonial people). An example of the attitude of the Indian people was their reaction to the appointment of Mr. Burrows as the new Governor of Bengal. He is an ex-railway worker and a Trade Unionist and those in London who appointed him thought, no doubt, what a gesture this was, what a sign of good faith. It was only when I was near the end of my tour that I realised this event had not been mentioned by any Indian! I remarked on this to one or two and they saw no significance in it—in any case when he had accepted a knighthood they knew for certain that it meant no change.

Yet amongst the middle class people were conflicting and changing opinions. At the time of the elections, for instance, when the “Quit India” campaign was at its height, Congressmen had had nothing good to say of the Labour Government, but, with the coming of the Cabinet Mission, all this seemed to change. Very many accepted their leader’s views that “freedom is coming this year” and gained a sudden faith in the sincerity of their British rulers. One can only be sure that in their hearts they still realised that India will only achieve her liberation by virtue of the strength of the movements within India itself and that, until all the different sections are united and working together, freedom will never be given them by their rulers.

At the same time as I put my point of view that the decisions of the Cabinet Mission could not mean independence for India, I remained convinced that the Labour Government is better for the Indians than a Tory Government—because the British people have an altogether greater chance of changing its policy. I explained how it is a Government based on the organisations of the common people and is not a collection of company directors and upper-class individuals with an eye on their investments. Its foreign policy is so bad and its attitude to India has not improved because the people have not woken up to the seriousness of the situation and so brought pressure to bear on it. Without this it has just fallen into the arms of the imperialists and is using the present administrators from the India Office and other “experts” who always have run India. True, they have at last accepted the fact that India wishes to be independent but not many of the Bengalee people I spoke to thought this was as a result of a change of heart—rather it was an inevitable reaction to the upsurge of the Indian people which could not be ignored.

Labour men were on the Cabinet Mission but behind them were these officials and imperialists who are so experienced in finding constitutional “solutions” to the Indian problem— “solutions” which help to divide the country and ensure their rule.

So I seemed to put all the responsibility on to the British people themselves and I had many discussions with Bengalees as to why Britishers had not aroused themselves more to achieve liberation for India. There is a considerable and growing section who clearly understands the issues, I said, and if one stopped any British working man in the street and asked him the simple question, whether he agreed with independence for India, he would say “yes”—if Indians thought that British people were flag wavers and thought of “their” Empire on which the sun never sets, they were wrong. But beyond that, our man in the street, like the majority of the common people, would not be very clear. He has vital ind important problems of his own—whether he will be able to keep his job, whether his earnings will go down, the difficulty of getting a house for his family, the shortage of food and cloth. These are very real problems in Britain (although I knew only too well that no Britisher is facing anything approaching the lot of millions of Indians). The reason the people of Britain are not more concerned about India is that they do not understand that their own problems, their own freedom and prosperity, are dependent to a large degree on the liberation of India. India is impoverished and Britain is in dire economic straits—yet between them they have tremendous natural and industrial resources. They do not fully understand that it is British rule itself that is holding back and strangling the development of India and that only a free India can be a prosperous India, and an asset not a liability for Britain.

The realities of British rule and the effects of this on India are hidden from the British people—one has only to look at the reports about India in the newspapers. They know that much is wrong, that there is poverty and oppression, yet they are given the impression that in India there is a measure of justice and fair administration such as they are used to at home (although democracy as it exists in Britain today has only been achieved by the past struggles and organisation of the common people themselves). They could hardly believe the true facts of police activities and the meting out of justice in India today—they are used to a regime where “law and order” means the protection of the individual. They are told there is some measure of democracy in India and they have heard of the elections going on.

Moreover they are given the impression that Indians cannot agree amongst themselves and that it is the British who try to do everything to reach a settlement. Indian politics seem so complicated to them and they cannot clearly see the way India can achieve her freedom without falling into anarchy and internal strife.

Real Hold on India

In the train on the way back to Calcutta I spoke to two Britishers—soldiers going home to be demobbed. They were disgusted with what they had seen in India—not with the effects of British rule but with the Indian people. The whole country seemed rotten and corrupt, and the first thought of those Indians with whom they had come in contact was to swindle them. They had seen mass enthusiasm for a figure like Subhas Bose who seemed to them to be a traitor on the side of the Japs. With it all they were “browned off”, soldiers in a foreign and often hostile land, and all they wanted was to see the last of the country and get back to their own own civilised home. They were not against giving the Indians their freedom, rather the country seemed to be in such an impossible mess that the easiest way seemed to be to give it back to the Indians and let them clear it up for themselves— although they did not have much confidence that they were capable of doing it.

How little did they realise the stark realities of the rule and exploitation being carried out in their name! I thought of them when, later on, I went through Clive Street, the business centre of Calcutta. Here were the names of those great British firms—Andrew Yule, Mcleod’s, Bird and Co.,—who have a grip on jute, coal steamer transport, pulp mills, insurance and such like in Bengal. The most important is jute— of 106 mills 97 are in the Indian Jute Mills Association and 84 percent are British owned. This is the industry whose exports are half those of the whole of Bengal, an industry

where profits of 50 per cent a year are quite common and which even reached 400 per cent, an industry whose aggregate gross profits are not far short of the revenue of the Government of Bengal. The workers in the mills, a quarter of whom are women, are shamelessly exploited and survive on a few rupees a week. It is these same mill owners who ultimately purchase the raw jute from the peasant growers whose condition we have already seen, and who control the market prices and therefore the destinies of millions of people.

The British economic hold is the key to the state of affairs in India today as in the past. In Bengal we have seen that it was as a system of collecting revenue that the Permanent Settlement was established. and that this is the root cause of the material and moral disintegration of the province. It was the way the British flooded the country last century with their cheap manufactured goods that finally ruined the village industries and the village sciety of India. Today it is British capital which has a hidden stranglehold on India. In spite of advances by Indian capital, this dominates in banking, exchange, shipping, plantations and such like—by means of the system of “managing agents” even enterprises which appear to be Indian are very often under British control. Most important is that the Reserve Bank of India, which controls all credit and has a similar importance in economic life in India as has the Bank of England in Britain, is in British hands and is controlled in the interests of British capital—not in the interest of the Indian people.

It is because of this also that the industrial development of India is held back, the reason that India is kept poor and backward. How could those who hold this capital afford to let Indian industry and banking develop, who would allow such competition to develop if they were in a position to

prevent it—as the British interests are? So we find a continual and sordid story of the thwarting of Indian interests at every turn—in particular heavy industry has been denied to India although this is the basis of any real improvement in the standards of life of the Indian people including improved methods of farming, irrigation and such like. How often is it realised that in the twenty years before the war the numbers employed in industry in India actually decreased! The same story was repeated during the war. Alone of all the Allied countries which remained unoccupied, India had no basic or important industries developed. Australia increased its steel production and made aircraft and built ships. Canada had many important industries established. But India increased her production mainly by increasing the number of shifts on obsolete machinery and the workers who were absorbed are now being thrown back on the streets—or to the villages.

The “Eastern Economist” (318-45) has bitterly summed it up. “During the war we were asked to do plenty of odds and ends but never the whole thing. We can repair ships, we can make small craft, but never the whole big thing. During the war we repaired 6,500 ships but we did not develop this into a regular shipbuilding industry . . . ‘Hindustan Aircraft Limited’ started as a manufacturing concern, and changed from manufacturing to servicing. The story in Ordnance and steel factories was the same. We could make everything and yet nothing. We were just general suppliers of anything and everything, but the makers of none. We had no system, no plan. Rather there was a plan—clear-cut and thorough—to prevent the industrialisation of the country in the post-war period.”

Indian industrialists had more success in the last war for it was at that time that the most important ones which exist

now first broke through—in particular some heavy industry was established. It is sign of the times that today the bigger Indian industrialists are coming to terms with the British interests, as for instance the Nuffleld-Birla scheme for making cars—a sign on the one hand of the irresistible urge for industry in India, on the other hand of new methods by which British interests can retain their hold. Also is the sinister fact that thus they both present a United front against the Trade Unions of the working people.

However, it might be pointed out that the affairs of India are surely not in the hands of a gang of British financiers. What of the Government of India? Does it not have considerable powers over industrial development? In fact are not many of the railways, originally British owned, now State Railways under their control? Yet we find it is the Government of India itself that has thwarted Indian industry and refused, delayed or whittled down under all sorts of pretexts, plans for the industrialisation of India. The explanation should be clear from what we have seen of Bengal. There, all important administration, all real power, is in the hands of Authority—from the Chief Secretary down to the District Magistrate and all the rest of the officials—and their function is to sustain the status quo (that is, British power.)

So in India as a whole real power is in the hands of British or British-nominated people. The administration in India, far from working in the interests of the people, is, in reality, but another means whereby the British interests retain their hold. Just like the bureaucracy in Bengal, the Government of India is by its very nature opposed to the forces of the people, the law it enforces is designed in the interests of British power and it is carrying on a tradition of 150 years of playing on the differences amongst the Indian people, retain ing the puppet Indian princes’ States and such like. So any talk of real freedom for India which does not involve the ending of this British economic domination is meaningless—it is interesting to reflect how rarely it is mentioned in the many statements from Britain reiterating good intentions about freedom for India. In any case the Indian people would be fully justified in seizing all the British capital and assets in India. They have been produced from the exploitation of India and are only held by the rnoneyed classes in Britain.

Moreover, Britain now owes India a sum of money referred to as the “Sterling Balances” which exceeds in amount all the British capital investments—and there are few signs that it will be repaid. These balances have become of paramount importance in the relations between Britain and India. They represent that part of the expenditure of the war in the East which, it had been previously agreed, was the liability of the British Government but which was, in fact, paid by India. The fact that they are so big, of the order of 1,500 million, is a measure of the extent of the contribution of India to the war. The only way the impoverished country was able to stand the strain was by inflating the currency and this reduced the standard of living to its present depths and was partly responsible for the present famine conditions and semi-starvation of millions. Perhaps many a British soldier would have had a different attitude to Indians if he had realised he was being kept and maintained not by Britain, hut by the labour of the poverty-stricken people he saw around him.

Thus the liquidation of the Sterling Balances (by handing over British capital assets in India) is bound up with the granting of real freedom to India. But could Britain stand the strain, is she not in dire economic straits herself? This very

common question implies that India must go on starving to save the British and it would be as well if those who asked it were to remember this. It is the same point of view as expressed by Mr. Bevin in Parliament when he said “If the Empire fell, the greatest collection of free nations would go into the limbo of the past—and the standard of living of its constituents would fall considerably”. Is not the reverse the truth—that only when India has freed herself from the shackles of British economic interests will she be able to develop and prosper and, when she does, she will need in tremendous quantity the very industrial equipment and machinery that Britain is able to produce, and she will be able to supply to Britain in ever increasing amount the goods and raw materials without which Britain cannot prosper. The only problem is the planning of this exchange of wealth, the only losers would be that class of British people which has its money invested in India. It is in this light that the settlement of the Sterling Balances in London must be treated—as part of the granting of freedom to India.

Way to Freedom

What is the way forward to a solution of the Indian problem? Why is the award of the Cabinet Mission foredoomed to failure? Indeed how is power to he handed over and India granted her independence?

To consider these questions it is necessary to bear in mind the policy of the present administrators of India. We have seen something of them in Bengal and one can hardly expect them to view with enthusiasm the prospect of handing over India to the Indians. They are enmeshed in an administration which has gained its strength and retained its hold

over this vast subcontinent for nearly two centuries by virtue of the backwardness and divisions amongst its peoples. They are part of that super-structure of British power in which the law and the civil service, the armed forces and the police, revenue and finance, trade and commerce, have been controlled for all this time in the interests of the foreign ruler. Today, as a result of their administration, the divisions amongst the peoples have so sharpened that solution seems well nigh impossible—except to those with the understanding that the future of India, as with all countries of the world, rests with the common people. And this is a thing a British colonial administrator will never be able to understand.

To them, India still remains the basis of British world power. Not only is it the largest unit under British domination, but strategically it holds the key to the whole of colonial South East Asia. Moreover it abuts the southern borders of the Soviet Union and in this respect also they have a long tradition of hostility to Russia. Indeed, are not the words of Rabindranath Tagore, written nearly half a century ago, still very true even in the changed circumstances of today? “From time to time we realise and are surprised that our British rulers, lofty in their sovereign authority and powerful beyond compare, yet live in this country in fear and trembling. We have felt, grievously, how the very anticipation of Russia’s distant footsteps gives them a sudden shock. For every time their heart beats startle there ensues an earthquake in the treasury, nearly empty, of our Mother India, and the little morsels which were meant for the hungry stomachs of the poor and exploited skeletons who are our people, turn in a trice into the cannon’s hard, iron balls, which is not exactly the kind of food we can easily digest.”

Today the British rulers have greater cause for fear and trembling. For within India itself there have developed tremendous movements for freedom from foreign rule. India has changed from a backward peasant country to a sub-continent seething with demands for liberation. The administrators must seek for new methods to retain their hold, new methods which appear to concede the demands of different sections but which will prevent them uniting on the common ground of complete freedom from British rule. Even during the war, they had anticipated this post-war upsurge and had been getting ready with their “solutions”. The earliest of these was prepared by Professor Coupland, generally assumed to be the greatest “constitutional authority” on India today and the Secretary to Sir Stafford Cripps on his “mission” of 1942. In his scheme a part of India is carved off as “Pakistan” and so would get the support of the leaders of the Muslim League. But it also includes “Princestan” by retaining the puppet Princes’ States which are in reality the Fifth Column of British Imperialism in India. Thus, with the remainder of India as “Hindustan” the country is artificially divided into three. Greater powers of Government would be given in “Hindustan” and “Pakistan”, but the calculation is clear. The country would be in such an unsettled state and there would be so many bickerings in deciding boundaries that the British hardly could leave—there would have to be some “independent” party to keep the peace. The key feature of the scheme, however. is the retention of “Princestan”. It is even pointed out how suitable are the Princes’ States for a chain of aerodromes across India and, as this is clearly the “safest” of the three areas, one can only reflect how modern

Figure 1: THE THREE INDIAS OF THE COUPLAND SCHEME. Black shows “Princestan” (with 63 separate autocratic states). White shows “Hindustan” and Hatching shows “Pakistan”. Compare with next map showing the different nationalities of India.

garrison armies can be airborne and how quickly they could be transferred to any source of “discontent” to restore “law and order”.

It must be conceded that the award of the Cabinet Mission comes very close indeed to the proposals of Coupland.

The main features are the same. The retention of the Princes’ States; the division of the remainder of India into groupings based on religious areas; no termination of the British control of finance or of the armed forces; a “weak centre” which includes the puppet Princes and which controls the vital matters of defence, foreign affairs and communications. In spite of the fact that the Indian leaders themselves are anxious to accept it and pass it off before their own people as a step forward, who would suggest it is any solution? Who can honestly envisage a real independent India as a result of this award? What hope does it hold for the common people of India, for the peasants of Bengal? Rather it envisages a bloody trail of civil war in which the British will be called upon to mediate every time.

The tragedy is that a Labour Government, resting on the radical and progressive sections of the British people, could be the means of such an imperialist award. India in this way is being turned into a real base for imperialist domination, a base which threatens not only the freedom of South Asia but British people themselves. The “experts” from the India Office, the lawyers, the “constitutional authorities”, who are so willing to give their advice to Labour Ministers, are themselves following the traditions of the old administration. Only when these are bypassed and the Labour Government reaches out a hand to the common people of India will a solution be in sight.

What then were the shortcomings of the Cabinet Mission and what steps must the Labour Government still take, if it is to help India to its freedom?

Firstly, there was no declaration by the Cabinet Mission that its object was to grant complete and unqualified independence to India. If the Labour Government is sincere it

must state that it intends to hand over all power to the Indian people and that this includes a settlement of the Sterling Balances and of British financial assets in India and the immediate withdrawal of British armed forces (for, in the last analysis, control over the armed forces is the ultimate strength on which the administration rests). The fact that within India there are great differences amongst her people is no valid reason for the continuance of foreign rule. These are India’s own problems and will be solved by the Indian people themselves—indeed they cannot finally be resolved with the British dominant in India, for their existence is the only reason the British are able to remain.

Secondly, all the negotiations on the part of the British were with a narrow section of the Indian people, the middle classes and the landed and industrial sections. It is one of the results of British rule that the mass of the common people are not enfranchised and have no say in the future of their country. Moreover these middle sections have themselves attained their present position mostly as a consequence of the British administration—as we have already seen in the case of zemindars and the middle classes of Bengal. While the leaders of Congress and the Muslim League are at the head of mass movements representing the aspirations of millions for freedom, yet they are actually opposed to the rising forces of the common people, the organised peasants and workers.

In this they were on common ground with their British rulers, and it was because of this common danger that they felt the British would be forced to come to terms. So both Congress and the League tried separately to force concessions from the British instead of uniting and putting forward common demands. To any British friend of India their behaviour was certainly a sorry spectacle, but the object of the imperialists

was achieved. The Mission was able to demonstrate to the world that the Indian leaders themselves would not agree, and so the British were able to adopt the pose of peacemakers trying their best to bring the warring parties together.

The bodies which are to take over power and which are to decide the constitution of the new India are to be based on the last Provincial elections—on restricted and complicated electoral rolls ingeniously designed by British administrators of the past to accentuate the differences amongst the people and to check the real expression of the common people. (In Bengal it is the European members who traditionally hold the key votes between the nearly equal Hindu and Muslim members.) This stumbling block can be swept away by the adoption of the elementary democratic step of a simple, universal franchise as the basis of the Assembly to take over power.

Then the common people would be able to make their voice heard and isolate and remove their own reactionary leaders.

From what we have seen of Bengal, can we have any doubt that the peasants know who are the real friends and enemies of the people? Would not a vote for all of them release a tremendous democratic response, just as it would amongst the working people of the towns? The Cabinet Mission, of course, gave the stock answer to this proposal that the electoral rolls would take too long to prepare. We can hazard a guess who supplied them with this answer—those civil servants whose efficiency and democratic sympathies we have already noted. We call be certain they did not consult the organisations who are close to the people—Food Committees (who already have the mass of the people registered on the basis of ration cards), the peasants’ organisations or the Trade Unions—nor have they cared to call for cooperation of all the various parties in the preparation of a nationide electoral roll.

However, the key to any step by a British Government to solve the Indian problem can be found in their attitude to the Princes’ States. Once again the Cabinet Mission adopted the imperialists’ point of view and treated them as if they had some divine right to a separate existence, and gave them representation side by side with the Provinces of British India in the proposed Union of India. Any democrat is aware that they are ruled by autocrats who refuse their people even the limited rights of the common people in the rest of India, and that they were created and are only artificially bolstered by British power. They are the “safest” stronghold of the imperialists and can be manipulated like puppets by their masters. (Even while the Cabinet Ministers were still in India, the people of Kashmir, the largest Indian State, gave them their answer, when there were widespread disturbances directed against the puppet ruler. These were countered, of course, by savage repression and mischievous references to the Red bogey.) Once again, universal franchise for all the people of India would be the surest way of sweeping away the States, for there is no doubt what would be the opinions of the State’s peoples if they were allowed to have their say. Universal franchise for all the peoples of India would have one further effect—the present artificial boundaries, both of the States and the Provinces, would be nullified. These boundaries bear little or no relation to the communities and nationalities of India and they have only arisen to suit the convenience of British administrators in the past. Once again the Cabinet Mission accepted these boundaries as the basis of their award. In fact they are a straitjacket artificially dividing people of the same nationality from each other. In India today we are witnessing the emergence of these different

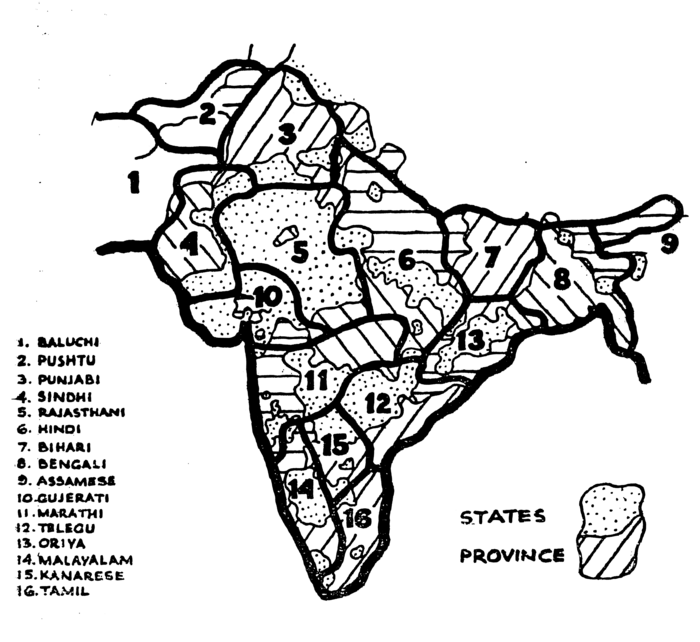

Figure 2: THE FUTURE MAP OF A FREE INDIA?

The map actually shows the extent of the main languages. It also gives an indication of the different nationalities that comprise India—for a common language is one of the most important features of a nation.

These national areas are here superimposed on the present artificial structure of India. Note the extent to which most of them are divided between two, three or more provinces and dozens of states. Could “Balkanization” be carried much further? (Bengal is one of the few cases where the present boundaries bear some relationship to the nationality.)

No mere “readjustment” of boundaries will solve the national problem of India. Nor can its different peoples develop until the Princes’ states are swept away.

By such elementary democratic steps the Labour Government could remove the hindrances to Indian democracy so carefully prepared by British administrators of the past. By doing so it would be imposing no “solution” on India, but would be assisting the common people to work out their own future.

peoples of India, and the removal of these boundaries would give the various nationalities the opportunity to unite and develop within their natural homelands. No doubt, in the free India of the future these different peoples will be interdependent and will have Assemblies of their own—whether they unite into a single Indian Union is for the Indian people themselves to decide. In this way the demand for Pakistan will be resolved into what it really is, a demand for freedom and independence for the different peoples and communities of India.

And these steps must be coupled with the complete and unconditional withdrawal of British power and the handing over of power to an Assembly of the Indian people. If the Labour Government refuses to do so and continues to remain in the arms of the imperialists, India will still achieve her freedom—her common people will see to that. But the British people will bear a serious responsibility for the untold suffering and misery that this will mean to India, and they will find it more difficult to capture the friendship of a sub-continent which has within it a fifth of all mankind and which is destined to play a most important part amongst the free nations of the world of tomorrow. For the forces of freedom are irresistible and, dormant for so long, the common people of India will triumph.

Then there will be a new and free India and a happy and prosperous Bengal—although this can never be understood by the British administrators and imperialists. But, amongst the common people of Britain, such words as those of Buddhadev Bose, a well-known Bengali poet will surely find a response:

“They do not know, my Bengal,

Of your ambrosia, the happy strength

You have churned through centuries,

The complete life, where ripeness is all.

You have been a victim of endless sorrow

Only when you were weak.

But in your strength you are inviolate,

Beyond conquests and invasions.”