The villages

“The evening lamps are lit no more.

Every little cottage in our village has its grave,

In the courtyards of the houses only jackals howl,

And no one knows who once lived there.

You, who can save and tend those who still live,

Come forward, save us, now!”—From a song of the Peasants’ Movement,

written after the famine.

When I arrived in an area I always sought out the leaders of the various organisations to help me see the village people. I soon learnt that Civil Servants and officials know very little of them. Individual Congressmen and Muslim Leaguers did what they could, but it was through the Kisan Sabha, the peasants’ own organisation and the various Famine Relief Centres, that I got to know them best.

Villages in Bengal are not easy of approach. Many are far from a road of any sort and one has to find one’s way among the maze of winding earth walls that bound the little fields. In the East of the Province only boats are any use during the rains, but after harvest peasants take their bullock carts across the fields and can cross the river beds.

For us, cycles were invaluable, although we did many a mile on foot. The roads that do exist give a shocking picture of neglect. There was a District Board road in East Bengal, for instance, which ran for some ten miles from a railway station and served, say, 200 villages. It was an earth embankment, raised above the water level in the rains, and was interrupted in no fewer than five places where bridges over small water courses had collapsed or disappeared. Bullock carts and the daily bus made huge detours over the fields below, for which tolls were eagerly collected. Some attempts had been made to rebuild the bridges but one had been built too high and so could not be used. Another had been rebuilt, but the embankment at each end had never been joined to the bridge! So there it stood, an island of rusting and useless steel, a monument to neglect. This sort of thing has gone on for many years, not only during the war—there were old peasants who could not remember the authorities ever having placed a single sod of earth to repair important roads. Often the villages appear as oases of trees amongst the rolling expanse of paddy fields. One peasant’s holding includes a number of these tiny fields scattered round the village, perhaps a mile distant from each other. To get the bare minimum for existence for his family he would have to have about 5 bighas (2 acres), or more than that where the soil is not so good, as well as a pair of bullocks and a wooden plough.

In the villages each homestead has four, five or more little huts grouped around a smooth mud courtyard, with perhaps a storehouse for the rice and an open shed, where the women husk the paddy by a crude arrangement of a wooden beam pounding the grain in a hole in the ground. The families are large, “joint families”, including the sons of the parents with their wives and children. Often, and particularly in Muslim homes, the courtyards are screened from outside view and the women stay inside in purdah.

The thin mud-plastered bamboo walls go quickly into disrepair, and many a home now has but its thatched roof left perched on a few bamboo poles protruding from the raised mud floor, the remaining earthly possessions of the tenant exposed to view. In the West of the province walls are of mud baked hard in the sun; in the East, surprisingly enough, corrugated iron is largely used. Now, many of the sheets have been sold for food and replaced by jute stalks and bamboo.

These homesteads may be close together in a village, as they are in the West, or, in the more flooded areas in the East, in straggling villages, each homestead on a little knoll, out of reach of the water. Perhaps nearby is a grove of mango trees, here and there a coconut, and little groups of palms, the juice of which is boiled and a sweet sugar made. All amongst

the homesteads are the straggling bamboo trees which are cut down to build new huts, to make matting or to weave baskets. And in many a village now there is undergrowth where mosquitoes thrive in the stagnant pools beneath. In the excavated “tanks” or ponds, the people fish and bathe sometimes with the cattle. The tanks, when neglected and uncleaned—more so when they are the only source of drinking water—are hotbeds of disease. In village after village, old broken handpumps stand unused and pure water is denied to the people because a few spare parts cannot be obtained. Burdwan was the only district where I saw most villages with properly functioning wells. Outside the village might be a mansion of the zemindar; amongst the homesteads, too, would be the homes of the richer peasants or the middle class. Perhaps there is a primary school—if it has not closed down—and in a bigger village, a post office and a Charitable Dispensary run by the District Board, where medicines can be obtained.

Hindus and Muslims

No doubt it was an event for the village when I came. Why should a ‘Sahib’ come like this to them? Yet when they realised that he, although a Britisher, was also a friend, there was no stinting of their welcome. Often I had to refuse the “hooka”, their communal pipe, as my stomach would not take it, and I had, perhaps, the cool milk from a coconut or a glass of tea made English fashion—for this habit has spread even to the middle peasants in the villages in the last few years. They usually found me a stool for, when one is not accustomed, it is not easy to squat for long periods on the floor—much less to eat in this position!

The boys and girls, particularly, were agape. They had heard of the British, but here was one in their village and drinking tea in Rahirn’s hut. The little ones, many with nothing on themselves, would stand and stare, perhaps at my shoes or my fine white shirt. The girls would shyly look at me from the corners of their eyes and trip off to tell the others, their sleek black hair shining in the sun.

It was easy to tell the status of the men. The poor peasant or the landless labourer, whether a Hindu or a Muslim, looked very much alike. All would have the same thin stooping bodies, very often with nothing on them except a piece of cloth around their middle. In a poorer village very many would be like this and some of them too, would be too ill and weak to be out working in the fields. But usually there would be a middle class Hindu or two, with their clean white dhotis and sandals on their feet. There might be the local school master, who would hardly be so prosperous, and perhaps the old postmaster, still carrying a tattered umbrella. The Muslims would wear their loose white trousers and a cheap cloth fez and occasionally there would be a prosperous one with his distinctive long, buttoned coat.

I did not often see the women folk. I perhaps would have a glimpse of them busy husking paddy, or there might be one in the distance going down to the tank to bathe, her coarse grey sari wrapped around her even under water; another getting water or sticking slabs of cow dung on a wall with her open hand to dry it in the sun–this is used as fuel where there is not sufficient wood. A woman in the fields would turn away if we passed by and lift the hem of her sari to hide her face. One of the effects of the famine, I was told, is that women can be seen about and working where they never could before.

I thought of the women when I had a meal. They prepared the food somewhere in the house behind, yet they never saw their guest. They would feed me well and as I did my best to manipulate the curries and the rice with my fingers, I would tell the man that this was not the daily meal of a poor Bengal peasant! How could a man feed his family on a few annas a day? What did they eat to keep alive? Rice and little more. Some fish if they could get it and a few vegetables now and then. Even the middle class usually had little more—perhaps they would get some milk and make sweet meats of curdled milk and sugar.

I also saw the remnants of those men who made Bengal famous in the past. The weavers, their looms silent now for want of yarn; the metal workers and the blacksmiths, who only get enough material to work for an hour or two a day. I saw one blacksmith whose forge was silent and he was weaving a mat with reeds for which he would get 14 annas in the market.

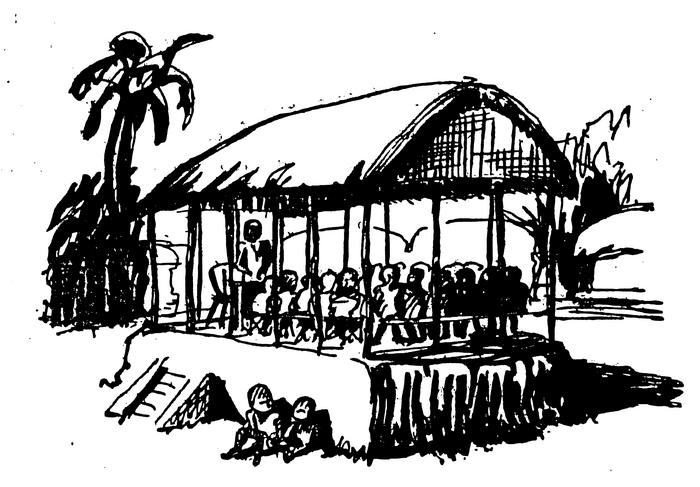

A school teacher might take me to see the village school. I remember one, an open sided hut say twenty feet by ten with a raised mud floor. About twenty boys and girls were

sitting on three benches and each bench was a class! The teacher went from class to class, asking questions according to their standard. Previously there had been a [literacy] class for adults in the evening but now they had no oil for lamps and so it had been abandoned. Over 90 percent of the people here could not read or write. This school had recently been opened by the efforts of the Kisan Sabha and was entirely self-supporting, run by donations from the villages and with no assistance from the District Board. Each child paid 2 to 4 annas a month and the teacher received a wage of Rs. 14 a month! For that he had received his training! How could he live? He was fortunate, he said, in that he had no family to support.

Originally there had been three primary schools in the surrounding villages but this was now the only one. Teachers like everyone else had been affected by the famine and could not get rice to live. Many left for temporary war jobs and got five or six times the money as a clerk. The pupils themselves had died, and now many cannot come as they have not the cloth with which to clothe themselves.

In the villages there is rarely a temple or a mosque, yet continually there are signs of the two religions and their effect on the peoples’ lives. Every evening, at sundown, the Muslims will carry out their prayers and salutations, facing West to Mecca. Little Hindu shrines are everywhere, under a tree or on some stones. Sometimes one sees a grotesque shape lying in the fields—all that is left of some stuffed Hindu image that had been immersed, as they always are, in the sacred water of the rivers and left here by the flood.

I remember arriving in a Hindu village after a walk of some miles across the fields as the sun was going down. It was a ‘Pujah’ day, and on the verandah of a house a crude image of a goddess had been set up decorated with flowers and there was an oil lamp or two about. Every now and then a man would go up and worship the goddess. The shrivelled Brahmin with his sacred cotton thread over his shoulder was in attendance and men would beat their drums and tinkle little bells. My presence did not affect the festival—everything was simple and free and easy. Half the village sat around and we talked of the embankment they had built to keep away the floods; they asked me about the peasantry in England and I told them, as best I could, that things were very different there—they had a trade union, like workers in a factory, instead of a Kisan Sabha.

Hinduism can, perhaps, be summed up for a Westerner, as rather a system of customs and superstitions than a religion in the European sense. It is the most flexible of religions but two important principles always stand—reincarnation, the belief that after his death the soul of every man is reborn in another being, lower or higher, depending on his actions in this life. Arising out of this, the second, the acceptance of caste—man has been born in his present station because of his past actions and so his status cannot be questioned.

True, many of the manifestations of this are breaking down, but it is still unbroken as regards marriage. A girl will never marry out of her proper caste. The main castes of priest, warrior and peasant, with untouchables beyond the pale, result clearly from an ancient feudalism, and history shows many examples of the struggles of the Brahmins (priests) to retain supremacy.

Hinduism then is not a religion that goes out to convert others to the faith. One is born a Hindu. Thus it is that, deep in the hearts of many a Hindu, is the feeling that Mahomedanism is an alien religion on the soil of Mother India. A Muslim has such a different faith. He is a fervent believer in Allah, the one God, and in Mahomed, his prophet who spoke the word of God. The Koran thus stands immutable, inspired and unalterable and it lays down the ways of life of a believer. I found that I could never talk to Muslims as I could to Hindus. With the latter I could discuss their gods, even laugh about them. For there are so many, each with a different story and very human failings and excesses. Different also is the position of women. In a Hindu family a daughter is a liability, for a dowry must accompany her in marriage. With the Muslims the husband has to make over something when they marry, and she has greater rights to inherit property. Yet her social standing is lower—amongst Muslims purdah is religiously enforced.

So these vastly different religions go on side by side and the differences mean altogether more than in any example of European history. Each creates certain differences in the way of living, in customs, and in outlook.

It seemed clear to me that Hindus tend to treat the Muslims as beneath them. Although in a village Hindus’ and Muslims’ houses would often be side by side, sometimes in the Muslim minority areas the Muslims would be grouped together in one part together with the untouchables themselves. And it is as difficult for a Muslim to eat in the house of a caste Hindu as it is for an untouchable—the place would be still unclean until washed and treated with cow dung. The same must have happened after I had eaten in an orthodox Hindu home. There, unlike a Muslim house, there would be separate dishes, for any food that is touched is unclean. I would ask them not to put too much in front of me as I knew that what I could not eat would be only thrown away! Even in an area with a majority of Muslims, the educated and middle classes are still Hindus. So also, with few exceptions, are the merchants and the zemindars—no doubt, as is so often claimed, the result of British policy. It is on this soil that the demand of the Muslims for Pakistan has prospered.

Yet they are all Bengalees. The Hindus, the untouchables, the Muslims have a common language and to a great degree a common culture. By uniting and arousing the peasants in their common interest, the peasants’ organisation is breaking down their difference and surmounting the barriers of caste.

In a Stricken Area

There were few signs at first that we are in an area seriously affected by the famine. The countryside seemed normal enough. The paddy was ripening in the fields, jute stalks were piled up, bleached by the sun, and the yellow splash of a field of mustard showed every now and then.

Few men were working as we made our way between the fields—only a half-starved cow tethered to a stick in the ground interrupted us and refused to move. Then, overlooking a decaying river, with rotting skeletons of boats still showing through the reeds, we saw raised patches of ground that once were homes. Their owners had sold out to the kulaks (that is, those big peasants who gained more land during the famine), and now they were God knows where. The ground their home once stood on is cultivated—but not by them.

Beyond were the gaunt remains of another homestead, the raised mud floors of the little huts not yet washed away by the rains.

Amongst the trees, huts were still standing and still inhabited. We walked into the courtyard of one of these homesteads. There was a deathly silence. In every one of a group of half a dozen huts were people too ill to come out. Some women crept to their doorways to speak to us. They were in rags and asked for medicine. Yet food was the medicine they really needed—nothing could prevail against disease in those frail bodies. It was unearthly to see such human beings. And through all the villages was this eerie silence. Not a baby cried, not a dog lived.

In another deserted group of huts everyone had gone for medicine to the relief centre. We looked in the huts and saw the possessions of these people. A little pile of rags—their winter clothing—two or three earthern pots, a few old bottles hanging from the roof and the tattered remains of a fishing net.

We came to a village where twenty or thirty young men and boys gathered round to meet us. They had been working in the fields and said they were the only male members still able to do so. Their fathers had either died or gone.

They showed us the remains of the village. Here had been a homestead—all signs of it had gone. There they had buried the family—and when they pointed out the spot I realised that under all those bamboo trees were graves, now hollows in the ground. They were everywhere and we saw them for several miles as we made our way around. Fifty volunteers from the Kisan Sabha had come to this village to bury the dead, and they brought with them milk and rice to save those still alive. “Two families were buried there.” “Forty people are in a single grave there.” They had buried 500 people in the villages around. In the single village where we were, they reckoned that of 700 people alive before the famine, 500 had died since then and more were dying yet.

Every now and then we would see some homeless destitutes. In the courtyard of a house a mother and her two little children with no possessions in the world, were sitting on a piece of bamboo matting, another piece propped up to shield them from the sun. One child was but a living skeleton, her stomach big with spleen, the other puffed out and covered with sores, his little eyes half closed. It did not need a doctor to see that they were past all hope. They would just stay and die. How many of these cold nights could they survive? Others had more life in them. A woman, sitting on the ground, had been given a dozen little fish and was slowly pulling off their heads while they were still alive. Her young

son had a few sticks and was trying to light a fire in a hole in the ground. A peasant standing by said this woman had a daughter who had strength enough to go out husking paddy and that she would be back soon with some rice. One could not talk to them—they were beyond all help or hope. They were too weak to notice our presence, and there was not even a movement by the women to draw their rags over their shrivelled breasts. And the children just sat still, without a murmur, and stared blankly out of their dilated eyes.

It was worse than a battlefield, this man-made death and misery prolonged and unending, with people living still amongst these graveyards, amid these lingering skeletons.

And kulaks and zemindars and moneylenders had prospered and grown wealthy out of this. Meanwhile the government and the officials soothe themselves and others that the famine is over, disease is conquered and they can close down relief centres and withdraw medical assistance as there is no famine. And in London, the Secretary of State blandly answers questions in Parliament on the basis of this information.

On our way back we pass a man demented, crying and wringing his hands. He passes on, oblivious to us in his grief. He had lost his son today, “My son, my son, the last one left to me!”

Two hundred years of British Rule! Citizens of the Empire! Do you not understand the benefits this has brought to India?