Land and Life

“Who among you will take up the duty of feeding the hungry?” Lord Buddha asked his followers when famine raged at Shravasti.

Ratnaker, the banker, hung his head and said, “Much more is needed than all my wealth to feed the hungry”. Jaysen, the Chief of the King’s Army, said “I would gladly give my life’s blood, but there is not enough food in my house.”

Dharmapal, who owned broad acres of land, said with a sigh: “The drought demon has sucked my fields dry. I know not how to pay the King’s dues.”

Then rose Supriya, the mendicant’s daughter. She bowed to all meekly and said: “I will feed the hungry.”

“How?” they cried in surprise. “How can you fulfil that vow?” “I am the poorest of you all,”said Supriya, “that is my strength. I have my coffer and my store at each of your houses.”

—“The Mendicant’s Daughter”, a fable by RABINDRANATH TAGORE.

It does not need statistics to prove that the peasants of Bengal do not get enough to eat—one has but to see them.

That is why, on the average, a Bengalee lives less than half as long as a Britisher, why also in Bengal, so may infants die before they even walk, and why all the poorer people have fever or disease to some degree.

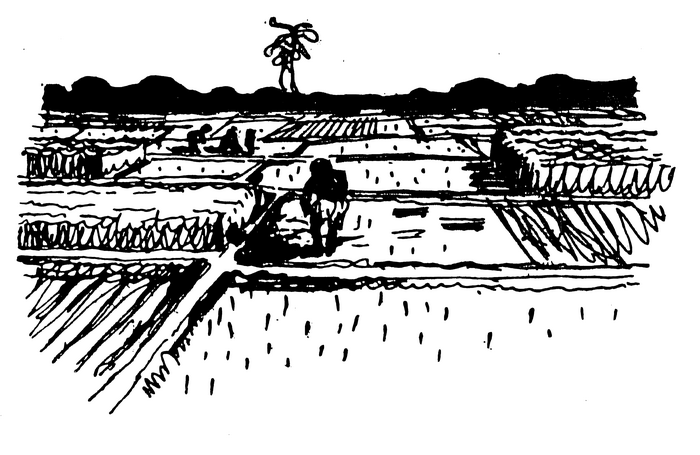

There are too many of them, the land cannot support them all, is a favourite rejoinder. How many who say this have seen the huge areas of land, once cultivated, reverting again to swamp, or the rivers and canals which brought water to the land, dead and dying? Do they know that from each acre still cultivated the yield of food is going down, that on the average one acre in Bengal produces but a half the amount of rice as compared with China or only a third as compared with Japan?

What have they thought when they see the farming methods of an impoverished peasantry, scratching the surface with a wooden plough, even burning manure for fuel because nothing else is available? Have they considered the crying need for industry, the millions who would be absorbed in developing the resources of Bengal?

Many times, as I crossed the little fields of the richest plainlands of the world, I pictured how so many of those tiny plots could be swept into one, how ideal were those rolling acres for large scale mechanised farming. The little villages could become communities of cooperative owners, water would once again flow to the land, untamed rivers would be harnessed and industry and mineral wealth developed. Bengal could be wealthy and smiling . . . But this is dreaming. For today the peasant does not even own the land he tills himself. The men who do, think only of ways and means of collecting rent and how they can retain their hold over their tenants. Yet, to the peasant, his land is his life—land means rice which keeps alive his family. So,

over all these little fields there is a never ending struggle for land and rice, for rent and life.

Why do the peasants submit? Because it is not in the nature of peasantry to revolt. A peasant who is the head of his family thinks primarily of that family, he has pride in its well being, he will struggle and sacrifice, he will sell up their possessions to save their land. But it is essentially an individual struggle. For the homesteads in a village are not united, each has its separate interest, some, relatively prosperous, are perhaps doing well out of another’s misfortunes.

A peasant is born oppressed and inherits debts and he accepts this as his lot. For he is illiterate and has not the means to know that anything else could prevail and his religion and his customs only perpetuate it—often, when the rains do not come or the floods ruin his crops, the cause of his misfortunes seems to him to be powerful Nature. Ranged against him all the time are educated and clever men with the law behind them who threaten him and, have the means, even the armed force to dispossess him.

At times however, the peasants’ struggle for rice and land becomes so sharp that all restraints are broken. Terrible dramas between man and man when all moral values go for naught, have been enacted in the remote and backward areas. I heard of one of these from an old Muslim peasant who had taken part. We were in his village where it had happened

several years ago.

“The crops had failed and we were starving. We gathered together to see what we should do, but our leaders were arrested. So the rest of us collected in the fields and we all went along to the house of the zemindar demanding rice.

“We squatted down outside and three or four called on him and asked for rice. ‘I cannot feed you,’ he said. ‘Your store is full of rice, rice from our fields,’ they told him. ‘Keep enough for your family and at least we shall not starve. For if we die, you also must die.’” With that he agreed. But while they waited he went upstairs and, through a window, shot nine of the peasants down below with a rifle that he had.

“We fled and assembled again. ‘Why did he murder us? We went to beg, not steal.’ Then we knew we should die in any case, so we came again to his house. But he had no more bullets left and some of us went in and dragged him out and killed him, with eight others also from his house, to atone for the nine of us lying in his fields.

“Next day the military appeared. Peasants from far around assembled to meet them. All we had were sheets of corrugated iron against their bullets, but we were too many for them and they left.”

Of course the rising was quelled and I heard later how it had been reported as “another communal riot”. For the peasants were Muslims and the zemindar a Hindu!

It was in this very village however, that they told me “It could never happen now—we now have our Kisan Sabha”.

Elsewhere, wherever their organisation was strong, there was this same feeling that now they could stand up to the zemindar. The fact that such brutalities are much rarer now than in the past is undoubtedly due in large measure to this greater awareness amongst the peasants and the influence of the liberation movements. How has this been achieved? By the peasants themselves understanding that their interests are one and that the only way to fight successfully against the zemindar is to unite against him. I was passing through some villages on one occasion with a well known member of the Kisan Sabha. The villages had no organisation but one or two had heard of what the Kisan Sabha had done and the peasants crowded round my companion pleading with him to take up their grievances against the zemindar. I always remember his answer “Yes, the Kisan Sabha will fight for you”, he said “but in your village you will be the Kisan Sabha. For remember, he is one and you are many”.

So simple and yet so revolutionary, for it entails breaking down their inborn prejudices and giving them a new confidence in themselves. This can only be done step by step and on issues which concern them strongly—not always to do with [the] zemindar. In any case he is probably away in the town and never sees his land which has been sub-let many times over and it is one of his underlings who is directly oppressing the peasants, and often as not he is the moneylender also. In a well organised area all the different types of peasants are united and conscious of their strength. Elsewhere the middle peasants might be the backbone of the organisation having come together on some such issue as exhorbitant charges for water from Government irrigation canals. In the stricken areas, the poor peasants and the landless labourers might be united against the “kulaks”—those bigger peasants who grew rich out of the famine and gained land and are now oppressing others.

Not all zemindars or taluqdars (sub-zemindars) would be oppressive to their tenants, although all, big and small, live out of the labour of the peasants, and are parasites of the land. Some of the smaller ones are nearly as impoverished themselves and there is hardly a more pitiful sight than one of these households. Wandering rather aimlessly about their dilapidated homes are two or three old men, perhaps with the sacred thread of the Brahmins over their withered shoulders. There are no young men left—they have all gone to the towns and those who remain try pathetically to keep up appearance with shoes on their feet and are often steadfastly opposed to the peasant movement. I was told of one of these who when asked his income, said his family now received only Rs. 28 a month from their land! Yet he was a zemindar and he also had the outlook of a zemindar. On the other hand some hold vast areas of land. One has practically a whole District— many times more land than any landlord has in England. While in the towns I often heard of legislation that protected the peasant and how this had improved his lot. But, in a backward area, what does the law mean to a peasant who cannot read or write, who has no money to employ a lawyer? There is an example in the extracting of “abwabs” by the zeminders—charges made by them on many pretexts and added to the rents. For instance, if a zemindar bought a new carriage he would recover the cost from his tenants, a wedding in his family would be charged to them, the peasant would have to pay a fee to sink a well in the land he himself tilled. This charges have been illegal since the very inception of the Permanent Settlement and there have been many laws since against them. Yet they continued on a colossal scale and official Commissions of investigation have pointed out that, through common usage, many of them have become incorporated in the regular rents. Nowadays, although zemindar still do levy ‘abwabs’, the practice is much less prevalent—their tenants have become more conscious of their rights. Legislation is of real value only when the peasantry is enlightened.

The Price of Rice is Death

In 1943 the Japanese were nearing the borders of Bengal itself. There was some shortage of rice that year and imports had been stopped because of the war. The general dislocation was increased by the bungling of the authorities. For instance, under their “denial policy” all boats were taken away from the peasants in certain areas for fear they would fall into enemy hands—in spite of the fact that they were the main means of transport in the villages and a necessity for fishing. It was under such conditions that the oppressors of the peasantry and the profiteers came into their own to reap a rich harvest from the deaths of their fellow beings. The 1943 famine was, in fact, a climax in the long process of the impoverishment of the peasantry under the Permanent Settlement.

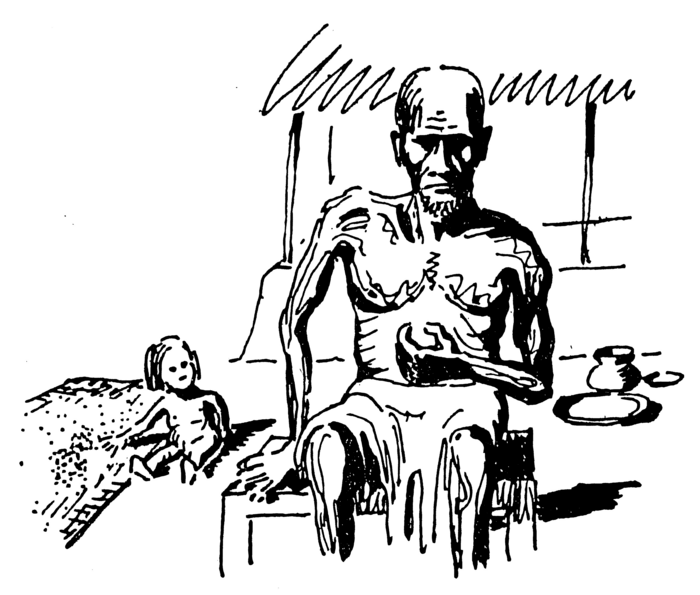

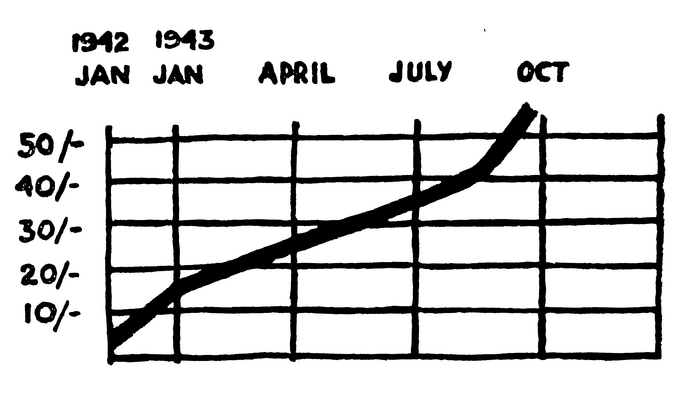

The shortage of rice amounted to about six weeks supply out of the full year—not more than had faced Bengal on previous occasions—yet three million people died of starvation and in the three great waves of epidemics that followed the famine. With equitable distribution people would have gone short but need these millions have died? They died because the price of rice went up and up, four, six, ten times, and the poorer people could not afford to buy. Those who died were the landless and poor peasants, the fishermen and such like—the very people who produced the food. Rice was always available for those with money enough to pay the inflated prices.

Even so, a peasant growing paddy in his fields need not starve—whatever the price of rice in the market—if he were able to keep back enough to feed his family throughout the year. But many of the peasants hold no land at all and they must buy rice to live. The sharecroppers who till the land of the zemindar or the moneylender, hand over half to two thirds of the crop to him and they are too impoverished to retain much of the remainder as food for themselves. As

Figure 1: The market price of rice per maud in 1942-43

for the peasants who do hold land, they pay much of their rent and debts in rice and after harvest have to sell most of what is left in the market or to the merchant for money with which to pay their other debts and to buy other necessities of life. So the rice stock passes into the hands of the merchant, partly through the zemindar and the moneylender and it is from these same people that the peasants and the town people must buy rice to live. It was they who held back and hoarded the stocks of rice and watched the price go up and up—only loosening it on the black market to those who would pay the price. Even the official Famine Enquiry Commission pointed out that for every human being who died in the famine, a profit of Rs. 1,500 was made by those who held the stocks of rice.

Not all the people I spoke to, especially middleclass people in the towns, would agree with this explanation of the colossal death roll in the famine. A local Muslim League leader told me the cause was the dislocation of transport under war conditions and that rice could not be moved to the stricken

districts. Elsewhere a Congress leader said it was due to the Government and the bureaucracy who themselves were hoaders and refused to release their large stocks of rice (a Muslim League ministry was in office at the time). I was also told that it happened because of the policy of the Government in procuring rice from the peasants and selling it later at much higher prices and that the people who gained out of the famine were the officials and the bureaucrats themselves.

All these comments were true enough but such people would not agree that private hoarders of all types were responsible to a very large degree for the deaths of their fellow Bengalees. For instance, when the Government procured rice it used private dealers and merchants as agents and so opened the doors to the stocking of the black market. When the Government was so inept as to attempt to control the price of rice without first securing the stocks, the inevitable happened and rice disappeared from the open market—held back by these same private hoarders.

Of course, people who gave these other explanations were not peasants themselves and they knew very little of their problems—one in fact was himself a merchant. They typified many of the middle sections of Bengal today who cannot see what stares them in the face—for these methods of exploitation and corrruption are accepted as normal in money making and in business and they themselves are most likely involved to some degree. However, when one is amongst the peasants in the villages, it is clear enough that the hoarders, the profiteering merchants and the black marketeers, no less than the zemindar, his underlings and the moneylenders, are the scourge of Bengal today. They were largely the cause of the deaths in the famine, they grew stronger as a result of it and their continued existence is one reason why Bengal has not recovered.

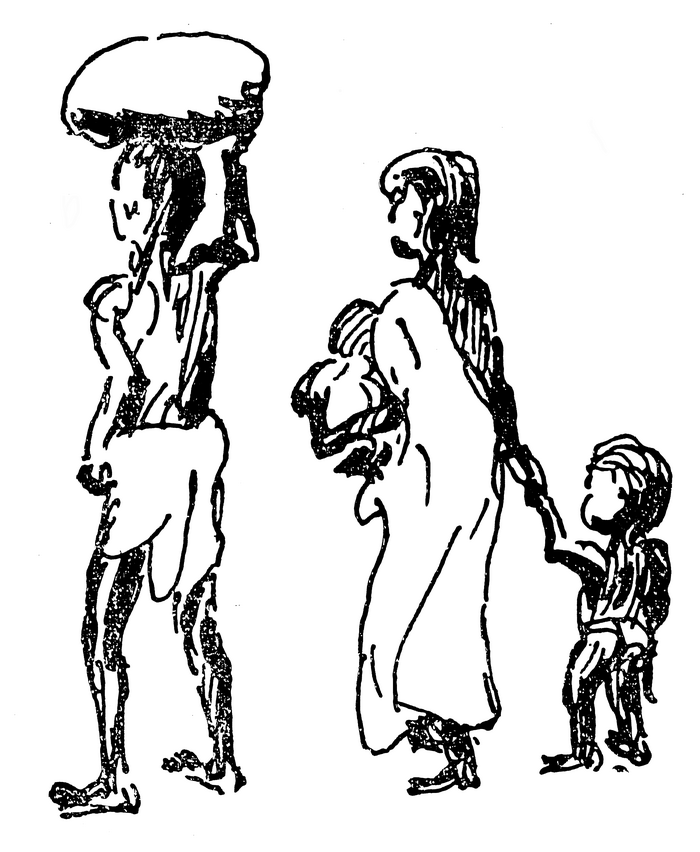

As for the peasants—faced with the rising cost of rice, large numbers had to sell their property and their rights in some or all of their land to that they could buy rice to live. Those already landless became destitutes without a possession in the world. Streams of them left the stricken areas and

those who have not yet died can be seen in many parts of Bengal today. Some who lost their land managed to remain in their villages and have become day labourers—they find work on another’s fields and earn anything from a few annas to a rupee a day. Others have become sharecroppers and cultivate their land for the moneylender, or whoever else it was to whom they sold the rights in their land. Some who left their home districts and survived, returned later. Two brothers, I remember, had just arrived in their village which they had left in 1943. They had trekked back from Assam and, except for the rags they stood up in, had nothing of their own. Before the famine their family had had several little fields and a homestead of its own.

The only ones who have gained in land are the same oppressors of the peasants—the taluqdars, zemindars, moneylenders and in some parts the “kulaks” or rich peasants. Over a half of the peasants are now landless, or have so little they have to work for others in order to survive. This large-scale transfer of land is another reason why Bengal has not recovered.

One of the steps the Government has taken and widely publicised, is to set up large centralised stores of rice which are to be released when the necessity arises and so will guard against famine. In the villages in which people are starving now, this seems meaningless and one can but wonder how much would ever reach the peasants and how much find its way to the black market. I thought of these huge stores on the two or three occasions when I saw the little communal rice stores in the villages arranged by the peasants themselves through the Kisan Sabha. These were on a voluntary basis and nearly all the peasants contributed. Distribution, as the need arose, was left in the hands of the local committee.

What confidence this demonstrated in their own organisation, what a change from the individual, backward peasants that once they were!

Very few peasants I ever spoke to had had anything from Government relief loans. One peasant in an East Bengal village who had received Rs. 25 in 1943, was being forced to pay back Rs. 50 now! This seemed inconceivable to me, especially when he told me that although he had only three bighas of land left, he was having to pay others to till it as he and his family were too weak and ill to work! It was only later, when I saw more of moneylenders and corrupt officials, that I understood how such things really could take place. There were also loans for cattle—these had died no less than human beings. Peasant after peasant complained that he could not till his land because his bullocks were weak or he had lost them—never during the whole time I was in Bengal did I see one whose ribs and bones were not clearly showing through his skin. In one sub-division, as an example, the Government loan worked out at 5 annas per family, and, as a bullock costs upwards of Rs. 150, it is not surprising that few peasants had even heard of these loans.

This season the crops have been badly affected by the weather—in West Bengal by drought and in the lower Brahmaputra valley by severe floods. In neither area has anything worth mentioning been done by the authorities to relieve the distress. In village after village in Burdwan District the peasants said they were only getting 25 percent of the normal crops because of lack of rain. A Kisan Sabha leader said the officials estimated the crop at 50 to 75 percent. He had been unable to get them down to see for themselves and had been told he was “scare-mongering”. I pictured to myself what would happen in a few months when the resources of the poorer peasants were exhausted. Some relief kitchens would be opened and very belatedly, perhaps after people had started to die off, some of the much publicised stocks of rice would be put on the market and some of it might find its way to the peasants. Another but a very tiny famine, too small to get into the papers, just a small part of the bigger one that will be sweeping India!

Peasant Producers of Jute

As well as paddy the peasants grow other crops which they can sell for ready cash in the market. The most important of these “money crops” is jute. Tobacco and sugar cane are also grown in some parts of the province.

In all corners of the earth jute is used for hessian, sacking and such like. Virtually all of it comes from the peasants’ flooded fields of East Bengal—there is nowhere else it will grow, nowhere else has the huge rainfall, the rich soil and the standing water which are necessary to produce the lengthy fibres. It is stripped, processed and washed for hours by peasants or labourers standing waist deep in water and then is dried in the sun and brought in bundles to the market.

I had heard there was a controlled price for jute but, in the villages and small towns, I saw peasants selling it to dealers for 7 to 8 rupees a maund—and bitterly complaining that it now costs them Rs. 10 to produce. It was later that I learnt that it was only the maximum price, of Rs. 12, which was controlled! Why then do the peasants grow it in such quantities? They do so because of the ready cash it brings to them. A peasant with a few acres will often grow just as much paddy as will keep his family and will cultivate jute on the rest of his land. When one asks a peasant how he decides the amount of jute he will grow each year, it is clear that it is just a speculation on his part. He has to judge what the price will be and how far it will pay him—or how much he might lose. Much seems to depend on rumours of the coming market prices, And there is not much doubt that the dealers encourage those of the right kind—for the more jute that is grown the easier it is to keep down the prices.

The market price of jute can mean the well-being or the impoverishment of millions of people. The Kisan Sabha is campaigning for a guaranteed minimum price to protect the peasant and high enough to ensure him a fair return. (There is a guaranteed price to the peasants for sugar cane delivered to the mill—although once again advantage is taken of the need of the peasants for ready cash and the rate hardly covers the cost of growing and carting to the mill.) It is common knowledge, even amongst the Government Jute Officers to whom I spoke, that the reason the Government does not lay down a fair price is that the market is completely in the hands of the Calcutta mill owners who manipulate the prices as they will.

These mills are mostly owned by British firms—we shall see later more implications of the jute industry in Bengal.

While in the villages I learnt something of the point of view of the peasant grower of jute and the odds seem very heavily loaded against him. He has to sell his jute quickly, as he must get the money—for it is traditional that at market time all those to whom he owes money, the zemindar, the moneylender, the Union Board, will press for payment. Also he has no proper store in which to keep the jute and it will deteriorate and discolour unless he disposes of it at once. On the other hand, the big dealers build up a reserve stock from earlier harvests and so keep down the price.

Above the dealer in the market is a whole hierarchy of middle men—it has been said that jute passes through more hands than any other crop—and each one of these has his profit, taken off the price paid to the grower. It was amazing

also to hear of the further deductions and allowances taken off the price. Charges are made for weighing, extra jute is always taken as a “dryage allowance”, deductions are made for festivals and such like. So, as with rice, above the peasant and living off his labours are layers of parasites. But there are important differences, for in the case of jute there is a highly organised industry at the top. The jute mill owners, the steamship and railway companies which carry the raw jute, the dealers, the brokers, the balers, the exporters, are all highly organised, are largely interconnected financially and have a powerful influence on the destinies of Bengal. They all live off the produce of the peasant and while he is the one who holds the real monopoly, he is exploited and swindled at every turn because he is backward and unorganised. That is why the growing peasant movement in the jute area is of such importance to the major industry of the province, the jute mills, and the stronghold of British capital in Bengal.