Who controls the control shop

“Learn to know this man.

Learn to hate and understand.

He stole and sold our food for gold,

He’d sell for gold his motherland.Hunger comes, a killing pain.

He smiles, stores up the peasant’s grain.

When thousands die in lightless gloom,

Gold brightens up his secret room.

When comrades rise in arms to fight,

He kills, to check our growing might.Can we who live forget our dead,

And let the traitor live instead?”—“THE HOARDER”, by a poet of the peasant movement.

I remember while in Calcutta reading the official statements in the Press, allaying rumours of a cloth famine, “Under the Rationing scheme cloth is being supplied at ten yards per head during the year” (and there were numerous protests saying how inadequate that was). Yet, in no case in East Bengal did I find a poor peasant or a labourer who had had more than one piece of 5 yards in 6 months for the whole of his family, that is but one eighth, or at most a quarter, of the rate at which we are told he is getting it. Elsewhere the best example was two pieces per family in 4 months or a maximum of half the official rate. If cloth is actually being released by the Government at 10 yards a year it but shows the colossal proportions the black market has reached.

Cloth is a necessity no less than food—in the cold winter nights weak and half-starved people can perish. In every area one of the foremost grievances of the peasants was that they could not get cloth from the Control Shop. “The women cannot leave the house because they have no cloth”, I heard on many occasions. There were peasants who said they had had to take their children away from school because there was not enough cloth in the family to clothe them. A woman, almost destitute, broke down and burst into tears once when

I asked about cloth. The murmurs and complaints from the others around left no doubt of the reality of the cloth famine in Bengal.

It is cloth for sails and dhotis which is supposed to be rationed and controlled. So is sugar, kerosene and salt. Yet I have been through village after village in the evenings which were blacked except for a glimmer of light here and there, because they could not get their ration of kerosene. I have seen some of the salt from the Control Shop which was so filthy that it had been condemned by the Sanitary Inspector as likely to cause dysentery, and yet for weeks no other was obtained.

On one occasion some peasants who had come in to market showed me their ration cards. Yes, the amounts they had received for several months were clearly marked—about a quarter of what they should have been. Here was proof enough for any officials and I told them so. One of them answered, “The Kisan Sabha collected 500 of these last month and took them to the S.D.O. He could not then deny the position. All he could say was, ‘I know it gets to the black market. But what can I do? You know as well as I do, that they are all corrupt.’”. This from the official responsible for all administration in his area and who is ever receiving greater powers.

Co-operative Societies

Controlled goods are supplied either through Co-operative Societies and Control Shops or through selected merchants and retailers. Unofficial Food Committees should also be functioning to control distribution, and watch activities.

Co-operative Societies have existed in some areas for many years under an Act of the Government of Bengal, as have Co-operative Banks for supplying cheap credit to the peasants. It is a surprise in backward Bengal, to see the solid buildings of some of their premises. The whole idea seems very enlightened—it might have been well intentioned—but peculiar things go on behind those walls. I had the example of a new Society, only recently set up. It was started by the S.D.O. himself and although much of what he did was against the regulations of the Act, it was undoubtedly perfectly legal, for, as we have seen, the powers of such officials are now practically unlimited.

The wholesale society for the sub-division was established with shares at Rs. 5,000 apiece. The only people who could buy such shares were the very merchants and blackmarketeers the Co-operative was supposed to counter. On the Committees of the Retail Societies, one to each union, the S.D.O. at first appointed a representative from each of the political parties, but since then they have been removed one by one on various pretexts and now all the members are Government officials! According to the Act, shares in the Retail Societies should be Rs. 2 each and payable at 4 annas a month. He made the shares Rs. 5 each, payable in one sum, thus making it impossible for poorer people to take part.

When, in addition, the private dealers selected to sell the goods to the villagers were not appointed by the Retail Societies under which they functioned, but by the Wholesale Society, the whole thing was seen to be a farce. The profiteers were in control at the top, they had appointed retail dealers to suit themselves (if in fact they did not actually own them) and everything carried on very much as before.

What did the peasants have to say about such Co-operatives? “They refused to issue ration cards unless we bought a share.” Thus food and cloth were actually being denied to the poor sections of the people. This rule was

only rescinded by the S.D.O. after long struggles. Another case: “They refused a ration card until we had paid our Union rates”. Members of the Union Board were running the Co-operative here. I confirmed from other sources that both these examples were correct.

It is clear enough where all the controlled goods go to, for the black market goes on naked and unashamed. With money one can buy anything, as I saw for myself. Corruption is rampant from the very bottom. I repeatedly heard statements that even when goods had arrived in a Control Shop they remained ‘under the counter’ until a sum sufficient to suit the shopkeeper had been added to the proper rate.

What of the people who expose these things? One, still a member of the Food Committee, had been arrested on a charge of dacoity after he had proved, by entering the man’s house, that a Committee member of the Co-operative Society had over 200 bales of cloth there. Another court case was in progress against members of the Kisan Sabha, who, in seizing hoarded bales of cloth from a merchant’s store, had become involved in blows. In neither case had the real culprits been charged for hoarding—indeed it is difficult to find a case in the whole Province, where a hoarder or a profiteering merchant has been charged before the courts.

Although this was the prevalent state of affairs there were still exceptions. Some Food Committees are functioning well and distributing as fairly as their supplies will show. One notable case was of a Cooperative Society which had been in operation for two years and which laid all its books before us, a very rare occurrence. Here there was a strong Kisan Sabha organisation and the S.D.O. had not been obstructive.

The result was a Society covering a Union and serving about twenty food committees and which obviously had the confidence of the peasants. In the villages I got no accusations from them against that Co-operative and although supplies were still terribly short, what did come was fairly distributed.

Food Committees

Food Committees were introduced originally to give a measure of popular control but now, in numerous cases they have been superseded. This was done by officials on the pretext of “greater efficiency” and as it is part of a similar process in other spheres it is worth considering one example in some detail.

I was in the house of the Secretary of a District Food Committee; he was a pleader in a small way and one of those honest individuals who still carry on in the midst of all the corruption. (I confirmed this from the villages—that is the only way to check an ‘honest’ man.) He was of no party, had once been in the Hindus Mahasabha and left it in disgust.

This was the story from his files.

For several months, all controlled goods had been distributed through non-official Sub-divisional and Union Food Committees. During this time they had made many protests to the District Magistrate about the slow and inadequate supply of goods to them, but trouble came when they submitted a detailed statement. This the Secretary showed me and I examined it at some length.

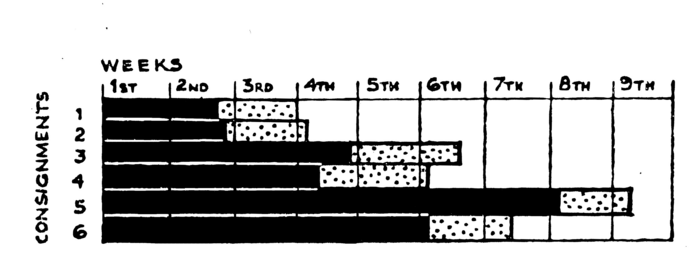

It was most revealing, and showed that the time taken for goods merely to be handed over by the Government Supply Department in bulk was about twice as long as the time taken for the Food Committee to distribute it to all the Unions. It was, in effect, an indictment of the bureaucracy and revealed the relative efficiency of the popular bodies. This could have

Figure 1: SIX CONSIGNMENTS OF CLOTH. Black shows the time taken for officials to hand over cloth in bulk after it had arrived in the District Store. Dotted shows the time taken for [the] Sub-Divisional Food Committee to allot cloth on basis of ration card holders, to divide the bales and to distribute cloth to about 100 Union[s].

hardly pleased the District Magistrate. At all events, at the next meeting of the Union Board representatives he proposed that cloth should be taken out of the hands of the Food Committees and supplied direct to the villages. All those present were unanimous in rejecting the proposal and they even decided to boycott the scheme if it were put into operation.

Afterwards the District Magistrate saw the Secretary and the conversation went something like this: “You were on the platform, you could at least have tried to persuade them to accept the scheme”, he said. “But they were unanimous, you saw their temper”, the Secretary replied. “Therefore I take it you are in favour of the boycott” was the rejoinder of the District Magistrate—this, of course, is an offence. They parted and following that he has been distributing through dealers and has taken it out of the hands of the Committee.

I then saw how distribution is working now, several months later. Cloth, for instance. The bulk supply of this

always has a great quantity of material useless for clothing, (although it is all included in the quota)—printed cloths, netting, expensive serges, etc. Previously the Committees had taken great care to divide this as fairly as possible. Now, naturally, the officials get the pickings at every stage and the unwanted materials arrive in the villages. He had figures submitted by him to the District Magistrate, which show that officials receive 4[0] percent of the total or about 16 times their share. Also a policy is being adopted (on Government instructions) to satisfy the towns first. Thus, the towns receive 16 times as much sugar as the villages.

He concluded with some bitter remarks on seed potatoes, which the peasants should be able to buy at controlled rates. A dealer had been appointed direct by some official in Calcutta to supply so many hundred tons for the District. These were bought in Central India, but as he said, for a relatively small sum, some individual from the railway staff can be bribed to ‘accidentally’ direct the wagons to a siding. The potatoes being perishable goods the contractors can do nothing else but sell them off, of course, at black market rates! Whatever actually did take place, the peasants of his whole District, were denied their seed potatoes at controlled prices, although they had actually been purchased by the dealer. In this sort of way the black market gets its supplies.