Let them die

“Come with me and I will show you,

Almost hidden in the shadow

Of an Indian night

Pavements strewn with human bodies

That with all the other shit

The authorities forget

Even to worry about.

Here’s one

Still lives, though all his flesh is gone.”—CLIVE BRANSON, a British soldier in India, killed in Burma, 1944.

We walked out of the little town to see the famine destitutes in their camp—those who were still left from the thousands who, in 1943, had streamed into this part of Central Bengal in search of food. As we walked along the road the night was falling and the cold already penetrating. We came upon the camp in the clear moonlight. Set in a clearing were five or six large bamboo and thatch huts—the huts already falling to pieces. The inmates crowded round us, many young women and little toddlers, and a few able-bodied men—altogether there were nearly 300 people in these huts.

The camp had been built with Government funds in 1944, that is several months after the destitutes had invaded the area. It had served to get them off the streets of the town and since then they had been virtually left to fend for themselves. One of the women told us the authorities even came recently to demolish the huts! But she and others had gone down to the Kisan Sabha office and one of the local leaders (he was with me then) had come straight up and they had all marched to the District Magistrate and he had had to rescind the order.

We looked inside the huts. There were no lamps—they got no ration of kerosene—but, by the flickering light of one or two candles, we could just make out the human beings lying on the floor. They were in all stages of destitution, the little children, with no cloth to cover themselves, huddling to the warmth of their mothers. We asked them from where they came. Mostly from Dacca District. One woman said she had had 6 bighas of land but the family had had to sell all they possessed and she had lost her husband on the trek from there. There were no complete families left. Some did not know whether their father or brother or mother had died or still lingered on in some other part—they were past hoping they would ever see them again.

“How do you live now”, we asked a middle aged woman who seemed to be the spokesman of the camp. “Some get jobs as day labourers”, she said and she proudly patted the head of her son, her only one left. He had worked on the aerodromes but, with the war over, that work is finished now. What about the rest? For there was only a handful of such able-odied youths. Then she pointed out to us what I had only heard of before. These women and girls were selling their bodies as the only means to get food—she herself had

been able to avoid doing so because she had had her son. I looked into the faces of the girls in the moonlight. Yes, many of their little ones were too young to have come with them in the famine—and there was not light enough to see the colour of their skin.

To such depths has been forced the peasant stock of Bengal, forgotten by authority and shunned by society. For later I was to find “respectable” people in the town nearby,

including leading members of Congress and the Muslim League, who hardly knew of the existence of these people except as a den of prostitutes and beggars. If it had not been for the man who was with me then, and others of the Kisan Sabha, many of them would not be living today—according to what they told us themselves. These people were their only friends, they had brought them food, they had fought for them against the authorities.

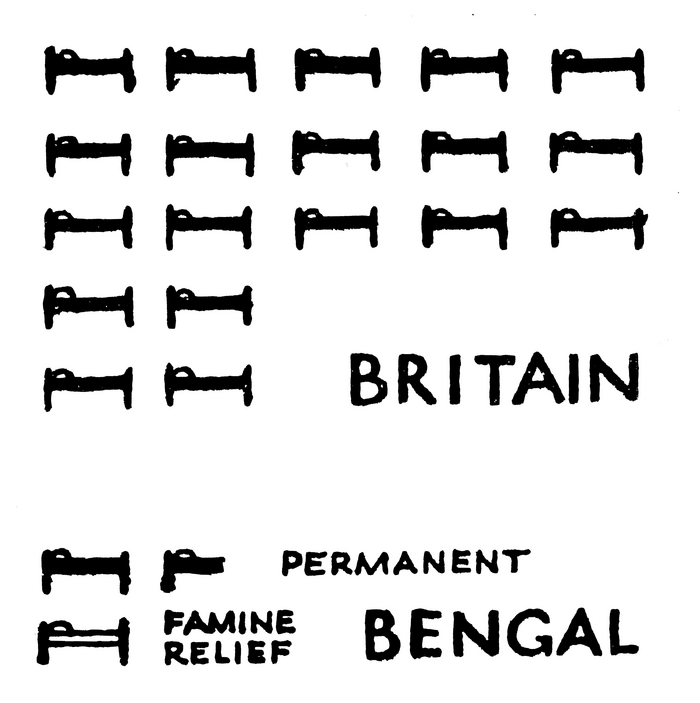

I felt very moved as I walked back with such a friend along the road. The little naked children followed, to see us go. Though they were trained in begging by their mothers, they never asked us for a gift. They also knew their friends. . . As well as such destitute camps, the Government provided Famine Relief hospitals in 1944. In one District I was in, there were six with about 200 beds. The permanent hospital beds are also about the same number, say one bed for about 3,000 people, or about twenty times as few as England. Is the Government developing these hospitals into permanent

Figure 1: Proportionate numbers of hospital beds

ones and taking the opportunity to improve the health facilities for Bengal? On the contrary, at the time I was there, their policy was to close them down as the need for them no longer existed. It was only later, but a few weeks before they were due to close, that they decided to retain most of them for a further three years.

The management of these hospitals affords an example of the anti-democratic methods of authority. I talked over this with the doctor in one of the hospitals. The hospital was typical of many of them—hardly a magnificent example by normal standards. It consisted of a series of bamboo huts with mud floors, but at least the patients had beds and blankets and mosquito nets. Originally it had been managed by the District Board with the S.D.O. Now, as a result of the policy of “efficiency” and Section 93, it is “provincialised” and run by civil servants under the department of the Civil Surgeon of the Government of Bengal.What is the difference? Previously, no doubt, it was not run as efficiently as it might have been and there was graft and corruption in its management. Now, however, there is every opportunity for bureaucratic muddle and corruption on an altogether bigger scale—hidden from the people and with little chance of exposure. For, however bad a District Board might be, it is a body of the people and its work can be exposed and checked to some degree. Certainly, supplies have now increased and there are more blankets, medicines even. But is this an argument for bureaucracy? Could not these have been made available before? Feeding also has shown some improvement. On the other hand the allowance for food per patient has been increased from 8 annas to 12 annas per day— altogether out of proportion to the improvement.

Why were these hospitals to be closed? (Only 15 percent of the beds were to be retained after three months.) I saw part of the answer when I visited others of them. The atmosphere was that of the old institutions of Victorian England—I had even heard one called a “slaughterhouse” by a past inmate. As well there was no proper system of finding patients— thousands might be dying in the villages but none would be crowding round their doors.

People’s Relief Centres

During 1943 gruel kitchens and mobile units had been organised by many unofficial bodies and, during the waves of epidemics which followed the famine, these had developed into established Medical Relief centres. I was talking to the doctor in one of these, a centre provided by the Bengal Civil Protection Committee. It was in two rooms in an old house near a village and the owner of the house had played a leading part in running the centre since its inception. Two cupboards and some tables comprised the dispensary and outside was a hand pump for drinking water. The doctor proudly showed me the microscope inscribed “To the people of Bengal from the workers of the U.S.A.” presented jointly by the C.I.O. and the A.F.L. It had proved invaluable—mainly for diagnosing kalazer fever—and was used also by three [or] four other relief centres in the neighbourhood. There were two regular assistants in this centre, volunteers who had been trained by the doctor, and who dispensed and issued medicines to the patient.

The patients were waiting outside the building—over a hundred of them. The men were in front and the women behind. Their condition beggars description. The women, frail and withered with their thin grey saries hanging loosely on their bodies, were sitting in little groups on the ground. (Even in such conditions the Hindu women kept apart and to themselves.) The bare bodies of the men were thin and bony and their cheeks had hollowed with hunger. The little children with protruding stomachs, were standing still and looking up at one with wide open eyes. Most of these people had malaria, nearly as many kalazer fever, and dysentery and stomach troubles were very common. They were all virtually starving.

The doctor dealt with an average of 200 cases a day at this centre. He would see these patients at the centre in the morning and the rest of the day would visit those in the villages who were too ill to come. When I went on his rounds with one of these doctors, I would see how well he knew the people and what help and hope he gave them. As we cycled

through the fields he would tell me, “There are three people dying in that home there”, “Eighty people have died in this village since the rains”. Yet such is the character of justice and authority, that I found of such doctors that I met, nearly all had been hounded and had spent their terms in jail for fighting for the people’s freedom.

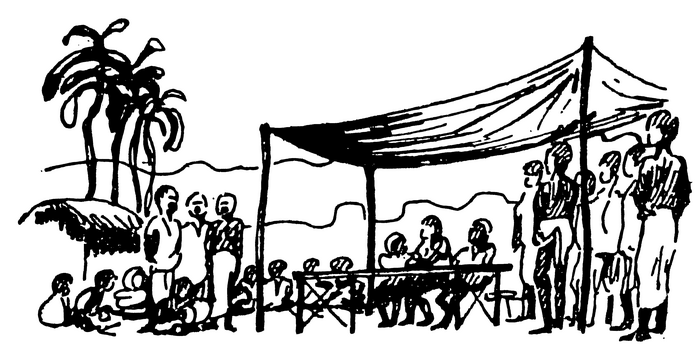

These centres give much more than mere medical relief. I found them to be the centres, in the fullest sense, of the lives and struggles of the peasants of the area. At one of them they had been told a British visitor was coming, and the local members of the Kisan Sabha prepared a welcome.

I had a special meal with the best fine rice and with vegetables and fish. As well they had made several special sweetmeats

in their homes the day before. They came from villages far around and it was there I met the village poet whose songs I had even heard in other Districts in Bengal. Two or three of them sang some of these songs for me. They tell of the beauty of their homeland, of the death and devastation of today, of the way in which the hoarders are waxing rich on the sufferings of the people. They tell of Congress and the League, of the fight against bureaucracy and authority, of how the Kisan Sabha is helping the downtrodden. These songs are sung far and wide, only two days before I had heard a blind beggar singing one in a little town.

We talked about their villages and about imperialist rule, of the Kisan Sabha and of Pakistan. I told them about England, how the common people are their friends. . .

There were four of these centres in this subdivision. As well there was one Government Famine Relief hospital and a few permanent District Board Charitable Dispensaries—three of these latter had closed, however, as they were short of medicines and it was difficult to get doctors as they were paid only Rs. 40 a month! All the unofficial centres were controlled by the Bengal Medical Relief Co-ordination Committee which had been set up in 1944. Two of these centres were run direct by the Committee, one belonged to the People’s Relief Committee, a body with wide support sponsored by the Communist Party, another to Congress and one, which had been run by the Muslim League, had been transferred elsewhere. They are supported by collections from all types of people. The Government had only helped to the extent of supplying rice to the relief kitchens for two months in 1943 and, after the medical centres had been set up, by the supply of quinine. At the time I was there because “epidemics are over” they intended to withdraw all assistance one month later. The relief centres are countering this with a campaign demanding that this decision be rescinded, and appealing for public support and donations to establish them on a permanent basis. They are determined that bureaucracy shall not be allowed to let the people die.

Who Knows The People Best?

When I was in the office of the Sanitary Inspector in the neighbourhood, I saw something of the way in which the Government obtains its statistics of disease and death rates.

This poor official, himself trying to live on Rs. 20 a month, is responsible for public health. He told me that it was the Kisan Sabha which had organised the volunteers for carrying out inoculations with cholera and other vaccines, when he had been able to get them. One of his jobs is to collect statistics and his room was full of graphs and figures.

How does he get them? From the village chowkidars in over a hundred villages. These illiterate, ill-paid semi-policemen, who often do not know or care about the people in their villages and whose object is little more than to give some figures, any figures, which can be entered on a form so that they can draw their pittance—it is on the basis of what these men say that the Government makes its statements. A recent one assured the world that, as malaria figures were down, the emergency is over. In any case this only covered a three monthly period and conveniently forgot to state that other diseases were so mounting that they threatened to surpass malaria.

Let us see what the doctors have to say, those doctors from the relief centres who are trained men and know their villages and are the friends of the people. It is revealing to know that the doctor who showed me the following report, was nearly arrested last year for making a similar statement! He had sent it by post to an Officer in the Government of Bengal but it somehow found its way to another department.

It was there stated to be a gross exaggeration and the doctor was charged with “creating alarm” and such like. The peasants in his area heard of this however, and over a thousand of them went to the police station demanding to be arrested too! In the face of this the charge was not pursued and he even managed to get an official down to show him that things really were as he had written.

The report I saw was prepared in Autumn 1945 by various doctors from the centres and covered a subdivision with several hundred thousand population. “The condition of health in the sub-division has deteriorated since last year”, it stated. “The patients who were attacked at the beginning of the epidemic had some resistance, whereas at present, people

are more devitalised and are suffering from chronic diseases with complications requiring a better type of medical aid and medicines . . . Due to this year’s floods, water borne diseases are on the increase . . . Immediate repair of hand pumps for drinking water is essential.

“Our survey shows that, of the total population, 95 percent suffer from some disease, mild or grave. 40 percent have serious ailments and of these 50 percent are in a grave condition and require constant and prolonged medical aid.

“It is proposed that . . . the existing staff at the centres should be doubled . . . medical expenditure should be increased to 500 to 600 rupees . . . the staff should have more equipment, cycles, torches, rain coats, etc.”

Whom are we to believe? These doctors or the village chowkidars? The organisations of the people or the bureaucracy?