Water in the wrong place

“Black cloud, come down, come down,

Flower-bearing cloud, come down,

Cloud like cotton, cloud like dust,

O let your sweat pour down.Bind cloud blind cloud, come,

Let your twelve, brother cloudlets come,

O cloud, drop a little water

That we may eat good rice.

Straight cloud strong cloud, come,

Lazy cloud, little cloud, come,

I will sell the jewel in my nose and buy

An umbrella for your head!Soft rain, gently fall,

In the house the plough neglected lies,

In the burning sun the peasant dies,

O rain with laughing face, come down.”

—Bengalee song of the Village Maidens,

by JASIM UDDIN.

Water is the life blood of Bengal. Its very soil has been built up through the ages by mighty rivers bringing down silt from the mountain ranges. The cultivation of its crops

depends on the intense rainfall of the summer monsoon and fluctuations in the monsoon can mean ruin to the cultivators- for there is practically no rain at other times of the year. So the control of waterways to drain away the floods and systems of irrigation to bring water to the land after the rainy season, have been recognised as important for centuries.

Many signs can still be seen of the canals and embankments which were still maintained under the Moghul Emperors.

Today, man, who should control nature, has lost his grip.

Over a hundred years of neglect and of terrible engineering errors in the construction of railway and roads, are turning huge areas into marsh and jungle, rivers are silting up and dying, elsewhere the sea water is creeping northwards and poisoning the land, other land is crying out for water. In a province where, in one District or another, the crops are rulned year after year by lack of rain or floods or some other calamity of nature, only one acre in 100 is served by Government irrigation canals. In one District, Midnapore, the acreage irrigated in this way actually declined by 80 percent during the 15 years before the war according to official figures. Elsewhere the small areas laboriously irrigated from rivers, ponds, and wells, often by human labour, do not touch the fringe of the problem.

The peasants are in a continual and almost lone struggle with the forces of nature. In the swamps and the stagnant land only the mosquito thrives and multiplies on its human victims.

The Seven Satanic Chains

Before 1850 the District of Burdwan in West Bengal was such a pleasant and healthy place that the wealthy people

of Calcutta had their country houses there and would stay to recuperate their health. Dr. Buchanan of the East India Company, commissioned to survey North and South India, was so impressed with the agricultural prosperity of the District in 1815 that he placed it first in all India. Yet suddenly, in the ten years after 1862, one third of the whole population died of malaria—many of a particularly virulent type called “Burdwan Fever”—and today it remains a most malarious District.

[[../images/25-river-in-flood.png]

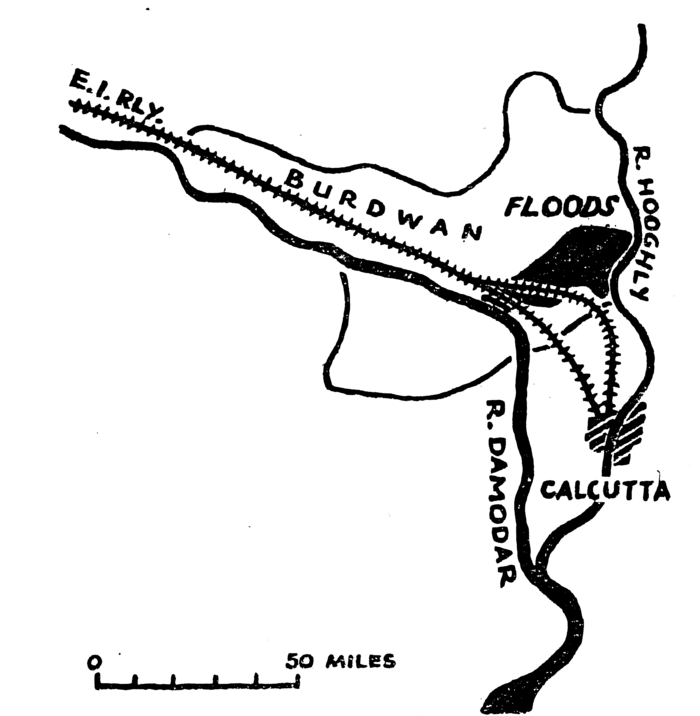

Why this sudden calamity? Because just before this time railway embankments had been built along the Damodar River with no consideration as to how they would affect the natural flooding of the river. Railways in Bengal are always built on continuous embankments to keep them above water

level during the rains. Along the Damodar, instead of allowing the flood water to find its way across the country and to drain away through other water courses and canals, they confined the river to a narrow course. The results were two-fold.

Deprived of its annual flow of water, the countryside went stagnant, prosperous fields changed back to jungle. Secondly, disastrous floods took place every now and then when the angry river tore through the embankments. In the rains the rivers here reach a tremendous size and bring down huge quantities of silt—previously this had been deposited on the land, improving the fertility of the soil, but with the river confined by the embankments, year by year this silt raised its bed. So the embankment had to be progressively raised and raised, and was periodically breached. The present seven embankments—railway, canal and road—are indeed Burdwan’s “seven satanic chains”, as they were so aptly named by Sir Herbert Wilcox.

In the soothing language of the Victorian officials soon after the first calamity, “a certain sense of insecurity prevailed amongst the peasants” and a scheme to control the floods by dams and reservoirs in the upper reaches was prepared by Army officers. Since then scheme after scheme has been produced, but nothing has yet materialised. All of these schemes had as their primary object the protection of “important interests”, that is the main railway lines and Grand Trunk Road—the welfare of the people of the District as a whole was hardly considered. The latest proposals prepared after the disastrous floods of 1943 go beyond this however, and demonstrate the tremendous possibilities of the agricultural and industrial development of this part of Bengal. The new dams would not only control the flow of water and prevent floods but could have hydro-electric stations producing

as much electrical energy as is at present used in the whole of the Calcutta area; the hills in the upper reaches would be replanted and the land cared for and would prevent the top soil being eroded and swept down the rivers in the rains each year; the rivers would be opened again for water transport from Calcutta even as far as the coalfield of West Bengal and Bihar; the peasants’ fields could be watered by large-scale schemes of irrigation. The Damodar Valley in fact could become another T.V.A. and Burdwan could lose its “satanic chains”.

At present there is haggling going on between the Governments of Bengal, the adjoining province of Bihar and the Government of India as to financing the construction works.

Also certain other “important interests” are involved and are having their say, the coalowners in Bihar, for instance, who claim their pits will be affected by the dams. Does the same fate as befell its predecessors await this latest scheme? Floods in the Damodar mean much more than breached roads and railways. In 1943 the river virtually changed its course and tore across thirty miles or so of peasants’ fields, finding its way into the Hooghly river and even threatening the Port of Calcutta. Officially, most of the country is supposed to have recovered—but stop a peasant and ask him. In one village two-thirds of the land was still unusable because old waterways, silted up by sand from the flood, have not been reopened. So the peasants become impoverished and food is denied to the people.

Certain areas of Burdwan are at present served by a system of Government irrigation canals. It was here the peasants’ organisations grew strong before the war after lengthy struggles against the high charges for water. These were finally reduced to under a half (during the war they were in

Figure 1: The lower course of the River Damodar

creased again and have just been raised once more to their original level.) This year the crops in these fields are thriving, elsewhere there is drought and a failure of the harvest. Every now and again, one sees little valleys in the parched ground which were watercourses before the Darnodar embankments were built. They are cultivated now, and zemindars—who own rivers also—are getting additional rent from them, so they are against them being opened up again.

I also saw a “little Damodar”, the Ajoy River, and the scene of the greatest victory of the organisation of the common people.

Figure 2: A dead river of Central Bengal

The embankment along this river had been allowed to get into disrepair and large portions had been swept away. For many miles one walks through derelict villages and straggling grass and reeds in sandy wastes that once were paddy fields. An Embankment Committee was formed from all sections of the people and, after a long campaign and after meetings, demonstrations and deputations, the Government had at last agreed to pay for the repair of the embankment and appointed a contractor—but not till June, the very month the rains would start and the floods come! Every official thought it was too late that year, but the Committee knew otherwise.

Immediately there was a campaign for labour and the Kisan Sabha toured the villages with the slogan “every peasant off his fields for a week to fill the breach”. They did it before the floods, two thousand men and women were working at one time in spite of difficulties put in the way by the contractor.

But they knew this was only a temporary solution and now they are campaigning for irrigation canals to bring water to the land and to control the flood waters of the river.

The sea is winning

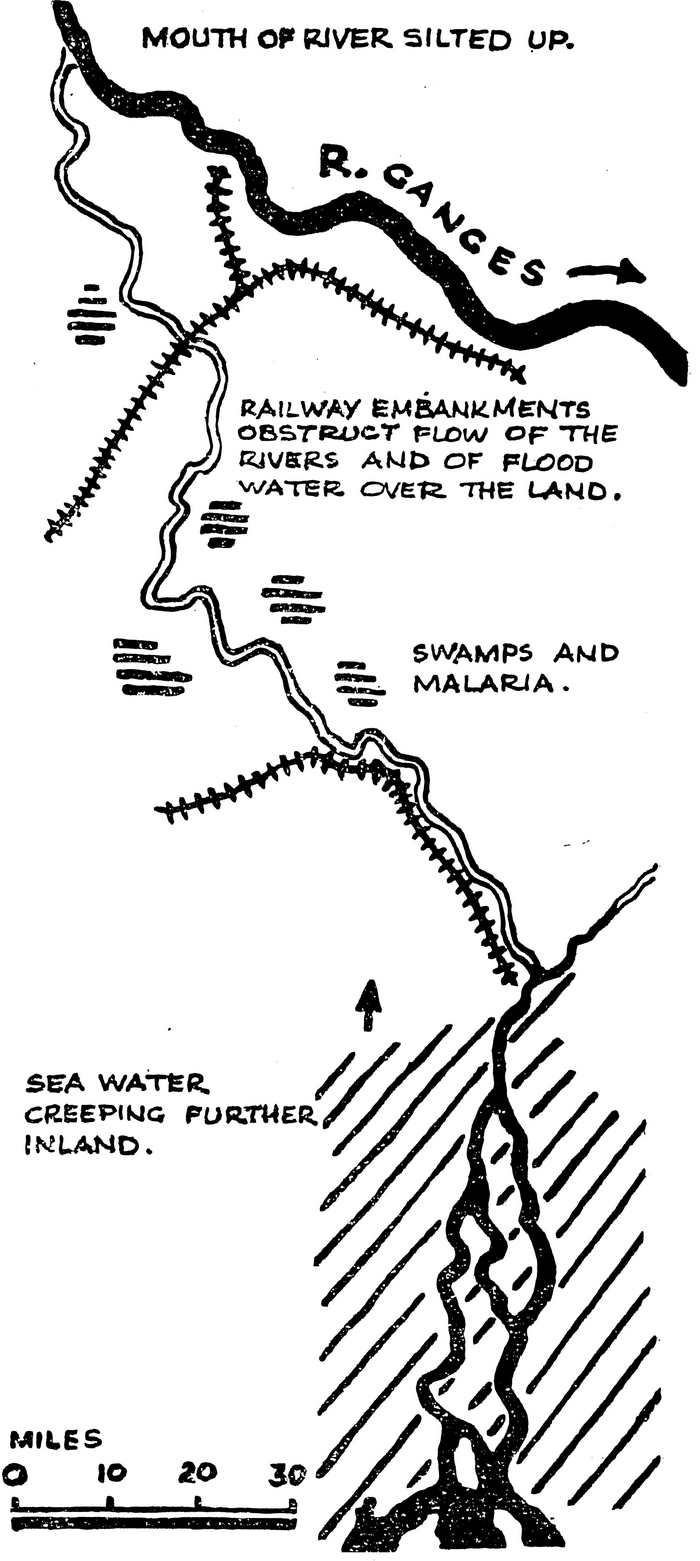

Jessore is the delta region of the Ganges. Numerous rivers branch off from the main stream and run southwards through the District. Today these rivers are dead or dying, just masses of hyacinth during the dry season and areas of standing water which cannot drain away during the rains. So the land goes stagnant and turns into malarial swamps, water transport has to cease, and fishermens’ communities die out as there is nothing in which men can fish. Further south, in the region where the rivers meet the sea, the saline water moves

northward year by year, poisoning the land, because there is not a sufficient flow of river water to sweep it out.

These rivers have been dying within living memory— they had been open before for centuries. The main cause is neglect of the land as a result of the Permanent Settlement.

The rivers always tend to silt up and so great sandbanks form during the floods where the rivers leave the Ganges. Who is there to keep these rivers open? An absentee zemindar never will—he has sublet his land and never sees it. The ones to whom it is sublet have not the capital resources, far less have the impoverished peasantry. So the rivers are just left to die. Also, across the level plains are miles of raised embankments for the roads and railways. During the floods water slowly moves across the land and these embankments become obstructions because the openings and bridges are not big enough or are insufficient. Time after time one sees a road or a railway crossing a river, the solid embankments carried out into the river bed itself and the bridge but a third or a quarter of the total width.

Nobody expected the Government to carry out major schemes during wartime; correctly enough they said they would support every practicable scheme which would “Grow More Food” by bringing land back to cultivation. But in practice they have been incompetent and obstructive. In some areas I visited, the peasants themselves had carried out more schemes than the Government departments, always after having first tried and failed to get official assistance. More than that I saw at least one official improvement of considerable size, which failed to achieve anything and was virtually a waste of money.

“Bodra Canal” was one scheme I saw that the peasants had carried out themselves and it had been proudly named

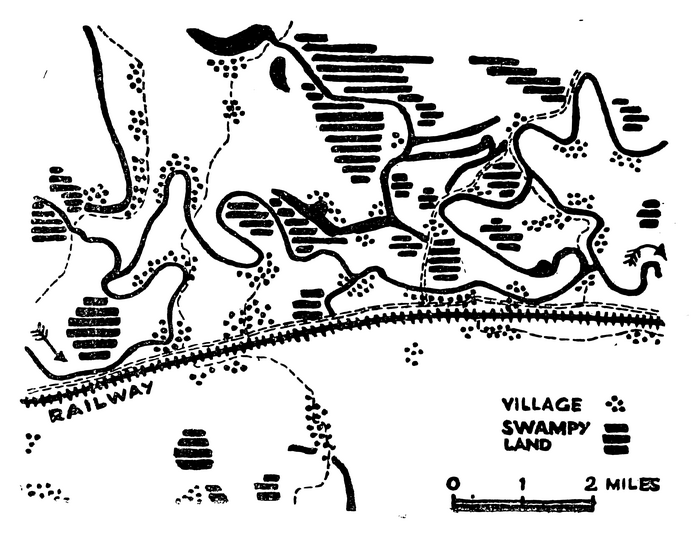

Figure 3: A dying countryside—a few square miles of Central Bengal.

Nearly all the water (shown in black) is stagnant and overgrown with water hyacinth. The arrows show the only river which is still flowing.

The fishermen in the villages lose their livelihood and become the first victims of famine. The huge areas of swamp are useless for cultivation, as well as being breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

The effect of the ralway embankment can clearly be seen. In this stretch of several miles there are no proper bridges or openings through which the water can pass.

after the local leader of the Kisan Sabha who had done so much to carry it through. At this spot the river has a great loop five miles round and completes a full circle except for a neck of land half a mile in width. It is across this neck that the great ditch has been dug, and it carries away the water from the sodden land upstream opening up this portion of the river again. Full 1,000 bighas of land previously useless are now cultivated and much more than that has been improved.

After a campaign in the villages for volunteers to dig the canal, the peasants, bringing their own tools and baskets, turned up in their hundreds. The only financial help was Rs. 1,000 from the unofficial People’s Relief Committee and this had enabled some of the destitutes to be paid a quarter or a half the normal wages and a camp was set up for them nearby. At the formal opening as well as the peasants who had dug the canal were well-known people of the locality. One can imagine the enthusiasm. When the rains came “the water roared through” as a peasant told me. I had also seen the peasant leader, Bodra. He was ill and exhausted with fever and malnutrition—in the past he had been hunted by the authorities and had had his term in jail. No wonder the peasants of the locality had recently contributed Rs. 300 to send him away to a hospital to get him well.

In the south of the District it was another story. A peasant took us in his boat to show its the embankment they had built last year to keep the sea water from their fields. Once this man had been prosperous. He still had his land, 28 bighas, and still had to pay the rent—but he got no crops. So he was finding daily work in a little port up the river. Everyone here was in the same plight and so in the famine very many had died and others were dying yet and many more were destitutes. The Kisan Sabha was strong in the area and last

year the peasants had rallied to build the embankment to save their fields. But as one peasant said, “We were too weak in body” and they only managed to complete 3 21 out of the 4 miles, so when the floods came, the water had swept it away. I enquired afterwards why the zemindars were not interested in preventing their land becoming useless. There were small zemindars here and the larger one higher up the river was waiting for them to become impoverished so he could buy them out! As a result he was obstructing the peasants with every means in his power.

Untamed Rivers

In Eastern Bengal there are also dead and dying rivers, but below the hills there are rivers of a different sort. There is a tremendous rainfall in this area and then the rivers become raging torrents and frequently break their banks, tearing across the country, leaving devastation in their wake.

Even along a stretch of a few miles, one can see five or six places where this has happened in the last ten years. One I remember was a great gap in the river bank 200 yards in width.

For miles behind, sand covered the earth and only tufts of spindly grass would grow. Virtually nothing is done or is attempted by way of controlling these rivers, it is just as if they were flowing through uninhabited jungle instead of cultivated peasants’ fields. I asked the peasants what happened after a flood, what assistance did they get from the authorities? None that they knew of. To be worthy of a Flood Relief Fund, it seems a flood has to be a great flood, big enough to get in the papers.

Farther away from the hills the rivers are somewhat calmer but they still eat through the banks and try to change their

courses. One place where this was happening there was a gap only 40 yards in width and over the last twenty years the river had been slowly carving a new channel. More and more of the water had been making its way across country forming huge areas of swamp and joining the main stream 10 miles lower down. As I walked around, the local people collected and I heard how they had built an earth embankment across the gap last year, but the water had overtopped it and finally swept it away. Here was a scheme on which the Government, by giving some financial assistance and helping these peasants, could bring back to cultivation and improve great areas of land. Yet, later, when I saw the official responsible, he had not even visited the area!

Controllers of Rivers

There is, of course, nobody controlling the rivers, they have got out of hand. But there are people whose interests prevent the problem being tackled. As I stood on a little railway bridge only some 15 yards in width and the peasants showed me how this bridge held back the water and affected the land for 10 miles upstream; when they pointed out the flood levels and suggested where new openings could be made in the embankment, I thought of the shareholders in London drawing their returns—for this was a British Railway Company. (Along these railways, too, the Company, since the famine, has allowed peasants to cultivate the waste strip of land along the foot of the embankment—but they get their rent, three eighths of the produce has to be handed over to the company.) In administration the needs of the railways always come first—that is when the point of view of the peasants is considered at all in high policy. Railways are important to

the authorities not only for trade and the returns they bring, they also have a vital military significance. Is it surprising that the peasants view with hostility these benefits of civilisation?

As for the zemindars who own Bengal, we have seen the interest they take in their land. There only remains the Government and its Irrigation Department. Clearly the engineers have not an easy task, controlling rivers is a difficult problem at any time, more so when they have reached their present state. Also these individuals are but cogs in a vast bureaucratic machine, but how far are they striving in spite of these handicaps?

I saw some of the officials responsible for this work. All of them told of the schemes and proposals that are in preparation. A dam and hydro-electric station here, a barrage there, the diversion of some river or another, afforestation in the upper reaches. True, there is a lot of surveying still to be done they said, and they were not sure of the exact sites.

This was all very interesting, especially when one heard of the mineral resources in the hills and one could begin to picture Bengal as it might be if its resources were tapped. However, I was just as interested in what was being done now, especially as I had seen something of the rivers for myself.

When I asked about this, usually I then heard of the technical difficulties, perhaps the whole of the rivers in the area depended on the diverting of the main Brahmaputra River back to its original course which it had left some centuries ago after an earthquake and that this was so difficult that it had not yet been decided how it could be done. What of the policy of “Grow More Food” and small scheme[s] which could be tackled to relieve the situation now? I told them of the examples I had seen. Some schemes like this were “under consideration”, some I had seen had not been heard of. Once one official grew a little exasperated and burst out that he was so busy and worked till 7 o’clock every evening “considering schemes”. He seemed blind to the red tape that bound him up and did not see that his work should be measured, not by the number of schemes on paper but by those he carried out.

Once I had more detailed arguments from an engineer as to why these small schemes were not carried out. Rivers which were trying to change their course should be allowed to do so, he said, nature was still building up the soil of Bengal. The Government was against any embanking, “just look at what happened on the Damodar”. What of the people that inhabited the area, I asked him, for how many generations was this to be allowed to go on? Perhaps the Dutch were wrong in resisting the forces of nature by keeping out the sea? Should not rivers be controlled as they mostly are in all civilised countries? True, Bengal’s rivers present special problems—an embankment in itself is no solution and if it is not properly considered it can worsen the situation. Yet here was an engineer who had retreated before nature and was taking refuge in arguments justifying this as a correct and technical point of view.