Tribal people

“.Some listen to the village talk. Others cannot hear

That, again and again. they call and say,

‘Help us out of our woes. Give us the right

To live like men’.”—From a song of the Peasant Movement

heard in the hills.

They can be seen from a far distance, rising out of the plains, the blue wooded Garo Hills which lie along the borders of Bengal and Assam. We cross the last barrier at their foot, the Someswari, a narrow river at this time of year, but in the rains a raging torrent, fed from the hills which have almost the highest rainfall in the world. The water of the river is calm and sparkling clear, with half a mile of sandbanks each side, blindingly brilliant in the sun, leading down to the water’s edge. We cross in a boat hollowed out of a single tree trunk, made by the people of the hills, and are in the area of the “tribal people” as the Bengalees call the inhabitants here. In all too short a stay I was able to see a little of the lives of a “backward people”, learn something of the methods of British administration of such border tribal areas and see the work of Missionaries amongst the people—more than that, to see how it was that such a backward area had recently become a stronghold of the peasants’ organisation. The belt of foothills here some 80 miles long, frequently called the “red belt”, is one of the strongest bases of the Kisan Sabha in East Bengal.

There are two main peoples here, the “Garos”, hill people proper, living in an “excluded area” directly administered by the Governor, and the “Hajangs”, in the foothills, whose area is “partially excluded” and where all enactments of the Provincial Government are normally enforced by him. I did not go to the Garo area—in any case permission has to be obtained to enter—but many of the people have filtered to the foothills and the plains below. Both these peoples are of Mongol stock, and very different racially from the Bengalees. The Garos are still tribal with a matriarchal system of society and a primitive religion which includes the worship of snakes and stones. The Hajangs have permanently settled as peasants in the foothills and have lost almost all traces of their tribal origin. They are Hindus now, but all of them are scheduled castes—untouchables.

Immediately at the foot of the hills in the plains there are Bengalee peasants and they are mostly Muslims, while the middle classes of the little towns and villages here are caste Hindus. On market days in these towns one sees the hill people who have walked for miles across the field carrying their produce in baskets on their heads or slung over their shoulders. A few are women. The Hajangs have straight-cut frocks

in brilliant patterns woven by themselves; the Garo women, surprisingly, wear skirts to all intents European ones and usually, in the hills, they wear nothing else besides. Of these people who live down in the plains, most are employed as menials and as servants.

The Permanent Settlement applies over all these areas, as it does to the whole of Assam—except that several years ago the zemindars in the higher parts of the hills were bought out by the Government, presumably because of the valuable deposits of coal and other minerals that are known to exist there. The holdings of the Hajang peasants are bigger than in the plains, 20 bighas or so is quite common. Their villages are similar, except that the huts are very low and are built up off the ground on short bamboo poles. There are virtually no roads to the villages and one has to walk across miles of paths between the fields or travel up the streams on boats.

Why are these areas “excluded” and administered separately? Officials will say it is because the people are backward, their administration is a special problem and they could not conceive of them governing themselves. So the hill people are left in their backwardness, more or less isolated from the world around—except for Missionaries who have their greatest strength in such areas. One wonders if such a negative policy is not partly due to a desire to be sure these areas remain “safe”—educated and enlightened people begin to question authority.

There are a number of Missions in this area, both Catholic and Protestant, and they have done much work in carrying the Gospel to the heathen. More than that they run schools, dispensaries and agricultural training centres which are open to Christian and non-Christian alike. For years they were the only force of enlightenment within the area; they produced an alphabet for the Garo people and the Bible has been written down in their language. One or two of the Missionaries I met had given the best part of their lives to these people and one could only have the greatest admiration for their faith. I asked one who had been there for nearly twenty years and was soon to return home, whether he felt satisfied with what he had achieved. “It is not what I have achieved,” he said, “I felt it to be my duty to do what I have done”.

However, one must ask whether their way is the right way, does it help to bring the people forward to real freedom and to become masters of their own destiny, to develop their own culture? From the Christian Hajang people whom I met, it seemed to have given them a false faith in the benevolence and goodness of the white man—it made them resistant to the demands for freedom from his rule. How could they come to know what has been carried out in India and in other colonies by men of Christian countries? As the only organised force in the area the Missions became, as it were, an unofficial part of the administration, with a considerable influence on the lives of the people.

Hajang People’s Own Movement

When one asks a Hajang member of the peasant organisation what it has done for him, the answer nearly always will be that they can now stand up to the zemindar; sometimes he might tell how they used to be treated as slaves and serfs, they would have to sit on the floor with folded hands when in his house—now his agent talks to them politely and offers them a chair! This is but the expression of an oppressed people in a new found confidence of their own strength as human beings.

They were oppressed in a double way; not only by the zemindars, but also by the rest of society because they were a backward people, different racially and because they were untouchables. (It is interesting to note in this connection that there is a considerable movement amongst them which attempts to show, on the basis of so called historical facts, that they are really of the “warrior” caste and claims that they should be accepted by caste Hindus as such.) Almost the only caste Hindus in their area are certain Brahmins who belong to a special sub-caste that allows them to carry out religious functions for untouchables. I was told how frequent it was in the past that an upper caste Hindu would behave in an orthodox manner; he would throw away his food as unclean if they walked into the room—in this sense they were worse than dogs, for he would not do the same with a dog. (Yet such is the strength of religious custom and tradition that a Hajang would not accept food from a Muslim.) One of the leading Kisan Sabha workers, himself a Brahmin, told me something of his experiences when first he went to their villages. On the one hand they were pleased the first time he ate with them— such a man had always spurned them before—but they were also shocked since it was against all their religious prejudices and customs and they resented it. He had to be very careful to know them first and win their confidence before he could expect them to accept him into their houses. Now, he said in the organised areas all this is past, Kisan Sabha workers are accepted everywhere and I saw much myself which confirmed this. In the movement Hajangs and Muslims are working together and whereas, in the past, women would never have left their house if a stranger were about, now there are as many as 50 present in a meeting of 200.

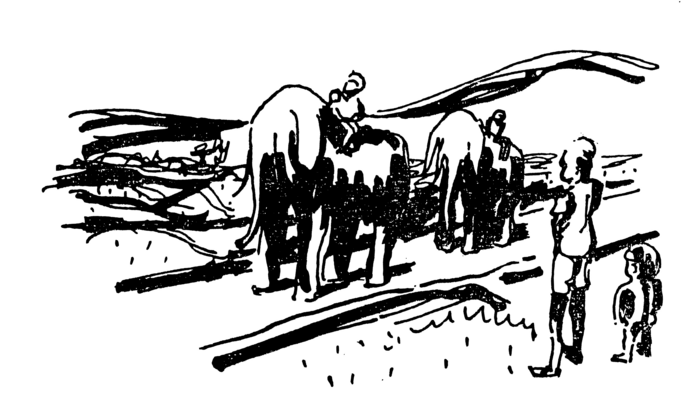

The zemindars here are mostly big ones, and since it was such a remote area, their oppression was especially severe and inhuman; it is only now that details are coming to light of earlier struggles against them. Sixty years ago, there was a rebellion which held out for a year, a rebellion against the practice of the zemindars of calling out their tenants in large numbers to assist in hunts for tigers and wild elephants, of course, without remuneration. It seemed that on one occasion a headman from a village was crushed and killed by an elephant in on of these hunts, and this was the spark that set the hills ablaze. Swords and spears were hurriedly made in all the villages; there were pitched battles with the hired forces of the zemindars, and villages were burned and looted.

Finally the rebellion was ruthlessly suppressed. When I was there I saw some of the huge tame elephants of a zemindar, used for his hunting expeditions, and they are against the

people in another way now. Their masters are refusing to allow the peasants to complete the digging of a small canal which would drain a large area and make it available for crops because this would affect the arrangements for growing fodder for these elephants. At present the Kisan Sabha has a court case pending to prove their rights to drain this swampy land.

The peasants’ movement first developed in strength in 1938 on a campaign against the illegal actions of the zemindars in demanding payment for rent in kind instead of cash, and against the “tonk” system under which the zemindar would only let his land on a yearly basis and the peasant would have no rights to hold it. After severe struggles in which the peasants’ leaders were arrested by the police, the zemindars were forced to accept the principle of property rights for their tenants. Then, the zemindars declared the hill areas as “reserved” to prevent the peasants collecting fuel and grazing cattle there as they had done for years.

The Kisan Sabha organised practical demonstrations against this when four or five hundred peasants would go to the hill slopes en masse and collect their fuel. A court case dragged on for a year and finally nineteen of these peasants were sent to jail for short periods.

Nowhere else did I feel such confidence amongst the peasants in their organisation as there was amongst these people; perhaps the very fact that they were so remote and backward has made them feel all the more keenly the urge for a new life and the need to struggle against oppression. I was proudly told that there are 16,000 paying members in the Hajang belt and that their quota by the next conference is 25,000. I saw members of the organisation who made it their job to go round the villages singing the songs of the movement and reviving the dying culture. Members have come down from Calcutta to help them collect information so as to piece together and write a history of the people. More than that, in some places they have organised and built up their co-operative stores for selling controlled goods; the Weavers’ Co-operative has been able to secure yarn to get handlooms going again. They were proud of the fact that not one person died of hunger during the famine in their area; they had collected food from each household for the people they were feeding in gruel kitchens and had helped to open five medical relief centres at the time of the epidemics. There was even one case, after epidemics had broken out amongst the cattle, when peasants from a number of villages farmed 400 acres together on a co-operative basis.

All this in an area the administrators make “partially excluded” because its people are so backward!