Pakistan and the league

“I say to the impatient youth, he not concerned with details of the scheme . . . Who knows what shape Pakistan will finally take and in what form it will emerge from the turmoil of the years?”

—A leader of the Muslim League.

An enthusiastic young supporter of the Muslim League will have a paper badge stuck in his cap with a map of India on it showing the parts he claims as “Pakistan”—the Punjab, Sind and the North West Frontier in the West, and 700 miles away, “Eastern Pakistan”, comprising the whole of Bengal and Assam. Mr. Jinnah and the League claim that this Pakistan should be a separate sovereign state and that India should be divided into two, leaving the rest as Hindustan. Since it put forward this demand in 1940, the League has undoubtedly had a phenomenal growth. It now claims to represent the mass of the Muslims—indeed that it is the only body that is entitled to speak on their behalf. This is as vigorously denied by its Congress opponents. How far is the League justified in its claims?

On one occasion I was in a town in a strongly Muslim area when two Muslim election meetings were in progress at the same time—one of the Muslim League, the other supported by Congress.

There was no doubt that the League meeting had the mass support. Several thousand men were squatting on the ground—a huge square of them. Their leaders, together with the candidate for the Provincial election, were on a raised pandal and the one who was speaking was invoking texts from the Koran and demanding that every believer support Pakistan for the defence of Islam. We walked through the town to the other meeting, called to support the candidate of the Krishak Proja, the “Peasants’ Party”, a party of “nationalist Muslims” who support Congress and are against the League.

People were thronging the streets—all the Muslims seemed to be out for the occasion. Some were up from the villages, middle peasants mainly. Everywhere were the loose white trousers and the fezes of the orthodox Muslims and now and again the long buttoned coat worn by the more prosperous ones. A bearded Muslim leader, with whom I had earlier had a long talk, passed in a rickshaw and gave me a gracious salute, his eyes sparkling with enthusiasm as he saw the crowds around. On a bicycle, and going our way to the “nationalist” meeting, was the local Congress president, a Hindu doctor. We crossed a little bridge. This other meeting was protected by police, armed police. A few hundred people were there. I heard the speaker demanding that the British “Quit India”, but it seemed ironical to be asking for this under the protection of their police. Several of the local Congressmen I had previously met were present and a considerable proportion of the audience were clearly Hindus and not Muslims. Young Muslim League students with megaphones were walking up and down outside the meeting, shouting “traitors to Islam”. I could not stay long. The atmosphere was too highly charged and, being such a strange visitor, I became a centre of attraction myself and I had no desire to precipitate an “incident”.

We got back to the League meeting. It was still on. This time the speaker was attacking Congress because, at the same time that it was demanding freedom for India, it was refusing it to the Muslims. There was a fervent and enthusiastic atmosphere. All around the main body of the meeting, people were wandering about and coming and going, it was as if the whole town were there. Sitting on a grass bank l had a long talk with two or three Muslim students on what they meant by Pakistan.

This was the feeling in a town, but what of the peasants in the villages? Whenever I spoke to a Muslim peasant and had the opportunity, I asked him the the simple question.

Had he heard of the Muslim League? What did he think of Pakistan? It was surprising how many had heard and were for Pakistan—at least in the majority Muslim areas in East Bengal. Never on a single occasion did I find one in favour of the Nationalist Muslims or for Congress. Why then did they support the League? If one asked them they could hardly answer—all they knew was that Mr. Jinnah and Pakistan meant freedom for Muslims and therefore should have their support. Some were confused. I remember, for instance, being in the villages the day after these same town meetings.

Two or three of the peasants (bigger peasants and themselves eligible to vote) had been to the two meetings and, on their return, had called together others from the village. They had all decided they should vote for neither party. Both had been calling on believers and quoting from the Koran. “Allah is one, they are dividing Allah”, they said, and they seemed to have a general disgust for all those people who, as they said, were never concerned to see them except at election time.

Whenever I asked a League leader or a student in the towns why Pakistan had such wide support, the immediate reply was that Islam is in danger from the Hindus and the only way to protect themselves was to have a separate state— this was their birthright and they would have it. Some times they would discuss the significance of Islam, how it is not just a formal religion but a whole way of life, that the conduct of every believer is laid down in the Koran, the word of God.

A leading Provincial member once even explained how all this made all Muslims into one nation and he pointed out that there are really four great nations in the world—West European including America, Soviet Russia, Fascism now disappearing and Islam.

I heard many opinions on the causes of Hindu-Muslim differences. It was pointed out how contrary were these religions, how they had different ways of life and the people a different outlook. Often these Muslims would be very bitter that the Hindus were repressing Islam. I particularly remember the occasion I sat in the local office of the League in a West Bengal town, one where Muslims were but a minority. The young student members had few ideas on what was involved in Pakistan, but they were fanatical against the Hindus because of what they had done against their religion. They claimed that for years they had been prevented by the Hindus from building a mosque, for instance, on the plea that its existence would be a cause of disturbances and communal riots. Many Muslims seem to feel there can be no flowering of their own culture while the Hindus are in their present position.

However, I usually pressed the point and asked whether there are not other reasons for these differences. Is it not true that economically the Muslims are oppressed? They would agree and would tell me different instances. Muslims in business told of the more powerful position of their Hindu competitors and students often said they knew Hindus would get the best of the jobs. Sometimes we discussed how far this was due to the policy of the British and the East India Company. Bengal had been conquered from the Muslims and quite naturally it was the subject Hindus and not the previous ruling Muslims who were given posts in administration and such like and became educated first. From this the Hindus developed into the middle class sections and today, are the first in business and in land. (Practically the overwhelming bulk of zemindars in Bengal are Hindus.) Moreover, Muslims told me many minor instances of how the Hindus slighted them. We have already seen that an orthodox Hindu ranks a Muslim with an untouchable and feels, in his heart, that Mahomedanism is an alien religion in Hindu Mother India, and these feelings are undoubtedly carried through in many minor ways. It is clear that often Hindus do not realise the bitter feeling there is amongst the Muslims—something they might say in all innocence will be taken by a Muslim as a slight directed against him.

This then is the background to the growth of the Muslim League. There is no doubt that, with its demand for Pakistan, it has brought about a mass awakening and, what is important, of a section of the people who, compared with the Hindus, were backward as regards their general prosperity, status in society, their hold in business and in land. So it has all types within its ranks or giving it support—peasants with an urge to end oppression up to astute business men who feel thwarted by the present position of the prosperous Hindus.

Its leadership is dominantly composed of landed interest in the countryside and the rich of the town. One one occasion I was in a town when a League meeting was broken up by a section of Muslim Leaguers themselves. These members were against their present leader whom they accused of being “pro-Communist” and working with the enemies of religion. However I saw something of the motive behind this incident and had talked with the individual in question. He was a staunch believer and a deep thinker but he was not afraid to give his support to the peasants’ movement even if there were Communists amongst it. Some at least of those who broke up the meeting were poor rickshaw pullers who acknowledged later they had been paid to do so. It was but a small example of how some reactionary sections are trying to remove present leaders and get leading positions themselves in the organisation.

Can Pakistan Save Bengal?

When I had a discussion with a Leaguer in a town, I would explain that, in Britain, Pakistan is little understood. Much is known of the struggles of Congress and there is great sympathy with its cause. Not so with the Muslim League. It has grown very quickly and religion is mixed up with its politics—a thing which is foreign to British movements and it seems to many British people that the League is dividing India and so is holding back its freedom. Must not all Indians unite to achieve their liberation?

Members of the League would always point out that, for them, brown overlordship is as acceptable as white: they are keen as any [Indian] for freedom from British rule but they want to be certain that this is not replaced by Hindu domination. They fear that if Congress, with its present policy, were to achieve its object, it would mean Hindu oppression.

Many of the students and younger elements agreed that they would have to work with Congress to achieve independence, but they could not do so until Congress had agreed with the right of Muslims to Pakistan. Some of the leaders, more used to party politics and negotiation, said the British Government should recognise the justice of their demand—this would become clearer as a result of the elections—and should take steps against the Hindus. Some even envisaged the possibility of some sort of Pakistan with the British still in India.

Thus they were relying on the British authorities to solve India’s internal problems. Did they really think the India Office would, or could “solve” these problems in the interests of the Indian people?

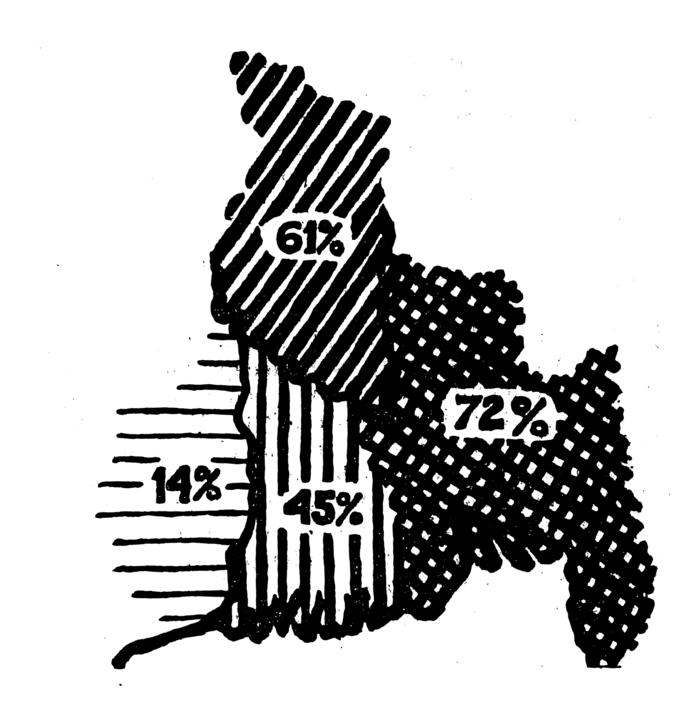

I continued, that even when one understood the background of their demands (for all communities have the right to their own freedom), there still remained the question as to exactly what they meant by Pakistan—in particular how it would solve the problems of Bengal. The Muslims claimed they were oppressed by the Hindus. Would not Pakistan only reverse the position?—I asked. How would they deal with the large Hindu minority in Bengal—especially in the west of the province where, in fact, the majority of the people were Hindus. Always they replied that, in Pakistan, there would be no oppression, the rights of all minorities would be safeguarded.

Figure 1: Map of Bengal showing the percentage of Muslims [in the populations of] the North, West, Central and Eastern parts of the Province.

Once again some of the leaders gave a constitutional answer. While in Pakistan there would be a Hindu minority, they said, in Hindustan similarly there would be a Muslim minority and this meant that the rights of each would be assured in the agreements that took place between the two parties. Others explained that with Islam there could be no oppression and, in any case usury was forbidden by their religion. I asked, would there then be no rich and poor in Pakistan, and does not being rich usually entail living off the labour of others? Yes, but the amount of profit and interest would be limited, no Muslim can see another human being oppressed. Once or twice I did suggest that this did not seem to tally with the fact that I had seen very little of organised efforts of the League to help the oppressed peasants in their daily struggle for survival, while at the same time many League leaders were living in comparative luxury in the towns. Their reply was—that these measures were only palliative—what they wanted was to change the system.

However these questions interested some of the students very greatly. One or two, in particular, were very concerned when I told them that I could not be satisfied with the answers their leaders had given me. They were sorry I had gone to the leaders at all and I thought it a good sign of independent thinking that they did not seem to have much faith in them themselves. We talked of the oppression of the peasants now, and of the zernindars and hoarders, both Hindu and Muslim.

But if Pakistan were to be a Muslim state, either the landlords would have to be replaced by Muslims for the state to gain real power, or they would have to be done away with entirely and the land given to the pea[sants. There] is no doubt the latter is what the peasants [would desire—]should not this be the demand of every Mus[lim? Further], we discussed West Bengal, a Hindu area. [How could] they in justice demand this as part of [Pakistan?] They replied that they did not want to see Bengal divided, they felt it was their Muslim homeland. I suggested there might be another reason—that the Bengalee people, Hindus or Muslims, think of themselves as Bengalees, they have a common language and they live and work together in the same land. Might they not be a nation in themselves?

When I spoke to such young people and thought of the struggle of the common Muslim peasantry against oppression, I felt that their Pakistan was a distorted manifestation of a genuine urge for freedom. It is obvious that it would not solve Bengal’s problems—let alone the problems of all the other parts of India claimed as part of the Muslim state. The leadership is far out of touch with the demands of the common people which it has aroused—to them Pakistan means the opportunity to carve large chunks out of India and to whip up the religious frenzy of the people. More and more they seem to be relying on a settlement with the British Government—a settlement that would have to be imposed on large sections of the people without their consent. The more this happens the further they get away from the masses of the Muslims and the more reactionary their organisation becomes.

What Pakistan does show is that the backward communities in India are on the march and that any solution will have to include freedom for them also. The fact that India does include many communities and nationalities, that indeed it is a multinational country, cannot now be ignored and the whole question of freedom for these nationalities and backward sections, is on the order of the day.